Cassidy Childs

Cassidy Childs is a research associate for International Climate Policy at the Center for American Progress. Prior to joining American Progress, Cassidy was an environmental justice graduate intern at the White House Council on Environmental Quality, working on the Justice40 Initiative. She graduated from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs with a Master in Public Administration in environmental science and policy. She earned bachelor’s degrees in political science and society and environment from the University of California at Berkeley. Cassidy is deeply passionate about bringing equity and sustainability to environmental and climate issues.

Learn more about Cassidy’s STEM journey through her conversation with our Education and Research Fellow, Swastika Issar:

Let’s go back to the beginning, could you paint a picture of your childhood for us? Do you have any siblings? What was a typical day like for you when you were growing up?

I grew up in Northern California, in a town called Santa Rosa. And I have one twin sister who is now an environmental engineer. My mother is from Pampanga, a province in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines. She emigrated to California when she was younger, while the rest of her family- her siblings and parents- are all in the Philippines. So, we would visit every year or so to catch up with my cousins and my Titas and Titos.

My mom works as a registered nurse. On a typical day, she would drop us off for school. We went to school on the side of town where she worked. We’d always do some after school activities and our mom would pick us up afterwards. Those activities were really great for our education. We had robotics clubs and science fairs- I think that’s where my love of science started.

On the subject of school, were there any subjects that you really loved or hated?

I loved it all. I know that sounds really nerdy! But I think the reason I chose an interdisciplinary field like climate change policy was because I loved English and writing. My day to day has a lot of writing in it. At the same time, I was really interested in STEM- physics and math in particular. That’s how I got into climate policy and environmental science. So, it feels like two different parts of my brain are always working in tandem.

Was there one person, or a group of people, who influenced your choice of this career path?

I can’t say I can pinpoint just one. I’m really thankful for the community of teachers that helped me along the way. I had a seventh grade English teacher who taught me that I could really write. My eleventh and twelfth grade physics teacher encouraged my love of science and math. My history teacher in twelfth grade really got me into political activism and caring about social issues, such as, climate change and climate justice. A thousand pushes in the right direction from many different people helped me in my journey. I think it’s crucial to have those teachers and those mentors at different stages of our life, all encouraging us in the path we envision and daring us to dream.

And did you pursue your interest in combining STEM and activism right away at university?

I started as a political science major at Berkeley, which was a lot more politics and very little science. But we had a wildfire in my hometown that year and that inspired me to think about climate change. I was also in an intro to climate change class at the same time and everything we were studying felt very real and personal for me. I felt like it was a good bridge for me to get into political activism and advocacy. I had always loved science, so it was a good return to STEM for me to learn about how our social, political, and economic world interfaced with our changing environment. That was the big moment where I changed from caring about social issues in general to focusing on climate policy.

I started out in a Bachelor of Arts program and by the end, I also had my Bachelor of Science. My Master’s degree at Columbia University was STEM certified.

Asking for our young readers who are thinking of a career in climate policy, what kind of courses did you study at university as an undergrad?

It was a mix of political science and environmental science courses. I learnt about how Congress works, how the executive office works, how bills are made into law. I also took climate change & environmental science courses, studied political ecology and global environmental politics. Reading all of those UN treaties is directly related to what I do today.

What came after you finished your undergraduate degree?

I really wanted to continue a career in climate change policy. It was this niche field that I didn’t know- when I graduated my undergrad- if I could even land a job in, and then the pandemic hit. The job search got even more difficult. But the truth is climate change* issues are not going away anytime soon. In fact, the environmental effects of climate change such as the fires in California continue to get worse. So, I decided to pursue a Master’s. The timing was quite fortunate that the Biden administration really does care about climate change. This led me to intern at the White House on environmental and climate justice. That’s how I landed my job as a research analyst for climate policy at the Center for American Progress after I got my master’s last year.

*Sometimes in mainstream media, climate change is projected as a big debate among scientists. In reality, over 97% of actively publishing climate scientists agree that the Earth is warming at an unprecedented rate and that human activity is the principal cause of current global warming and climate change.

Could you maybe tell us a little bit about what your day to day looks like?

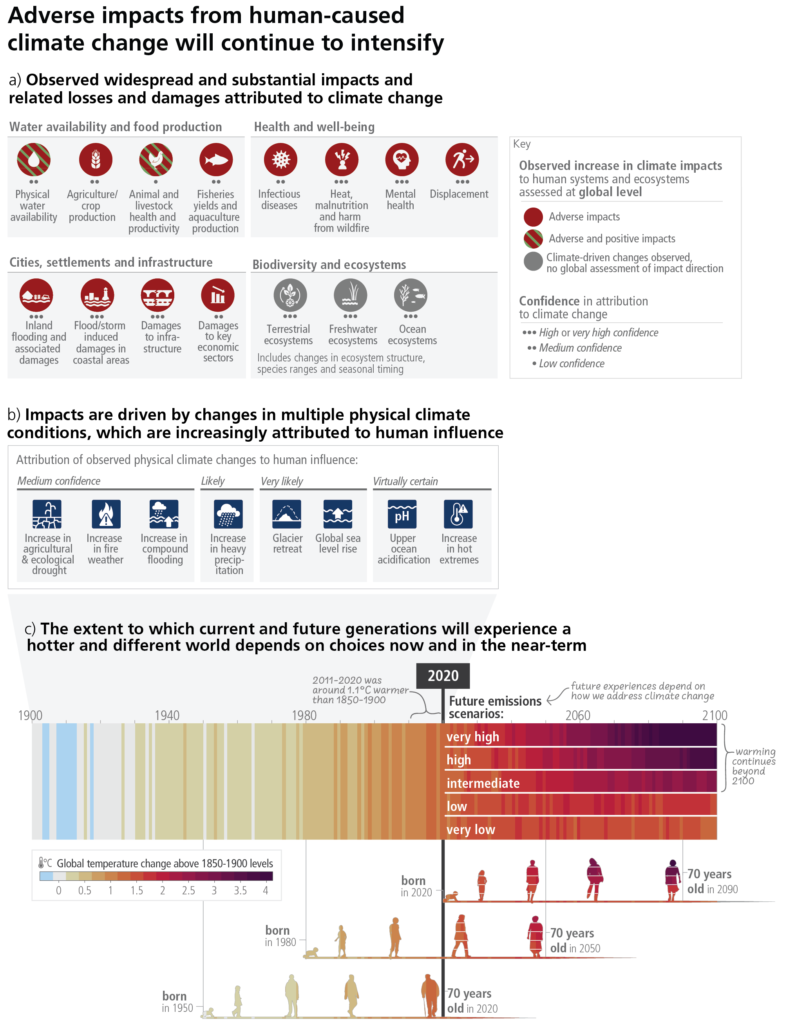

My days are quite varied, depending on what my assignments are that week or month. For example, the UN IPCC Climate report was released last week, this is the synthesis report for the sixth assessment cycle. A lot of my work last week was reading the work of hundreds of scientists on what the state of our climate is and what we’re expecting in the next decade of policy making to make sure our planet remains, quite frankly, livable. My work revolved around rapid response uplifting on social media, sharing the IPCC report, and its briefings to my team. I also wrote an article about losses and damages from climate change, particularly for climate vulnerable countries. So, I released that at the same time that the IPCC report came out. I focus on advocacy for what the US government’s doing on climate change, bilateral relations between the US and other countries such as India or the EU and how they could align their energy or climate policies. Figuring out where our policymakers and decision makers can find alignment is also part of my job.

It’s so incredible how much our politics, economics and history have shaped the world that we live in now, not just from a societal point of view but also the natural environment. And voting is such an essential part of exercising influence over what the future might look like…

Exactly. I know so many people who are discouraged by the political systems that they live in or believe that participating in the United Nations doesn’t actually work. The way I think about it is that silence won’t help, you can’t boycott political systems. Because then you’re allowing other people to make choices that will influence your life. Even if you think that the systems don’t work perfectly, we all need to participate in it.

Does the work that you do influence decisions at an international scale?

I wish I could say that the US is the most productive country in international spaces when it comes to implementing environmental policy. Oftentimes, my work involves encouraging the US to either work with countries or find creative solutions for low-income countries that can’t represent themselves equitably at these international conferences. I think that finding ways to build the technical capacity of those countries so that they can have their own scientists representing their interests at international platforms is very important.

Does the Center for American Progress work exclusively on climate science and energy?

The Center for American Progress or CAP, as we like to call it, is a think tank and a nonprofit in Washington DC. CAP works on a lot of different issue areas, basically anything that’s related to politics. It could be access to healthcare access, reproductive rights, environmental issues or gun control. Issues that Americans care about. I work on International Climate Policy in our Energy & Environment Department.

What are you most excited about in your current position at CAP?

I work on loss and damage in our international climate justice portfolio. This year, the loss and damage fund that was decided at COP27* is going to operationalize by the next climate conference in November. We’re seeing developed countries really take the concerns of climate vulnerable countries seriously by considering different financing solutions to support the technical capacity of vulnerable countries to become more resilient. And that really speaks home to me. The Philippines is one of the most climate vulnerable countries in the world. So having their concerns addressed at the global stage is exciting for me.

*Conferences of the Parties (COP) of the the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) are annual conferences that serve as the formal meeting of the UNFCCC parties to assess progress in dealing with climate change

What is loss and damage? Is it different from adaptive or mitigative measures against climate change?

Climate change mitigation aims at preventing emissions and adaptation aims to minimize the impacts. ‘Loss and damage’ sits separately from adaptation and mitigation. The term refers to everything that’s lost due to climate change. For example, Super Typhoon Haiyan, in the Philippines in 2013 was one of the costliest storms in world history. Preventing countries from falling into debt, or ensuring they have the financing to address all of this loss and damage is crucial.

And this irreparable loss and damage is expected to expand in scope and severity in the years to come…

Absolutely. There’s a perfect graphic in the UN IPCC report that came out last week. It shows people born in 2020, their lifespan and their comparative climate risk, compared to previous generations. It really drives home that people born today are not born into the same world as people born even fifty years ago.

What are your plans for the future?

I’d like to continue working on climate resilience, climate policy and justice. It’s really exciting, the work that I’m doing, and it’s desperately needed. So much of climate policy in the past has excluded climate vulnerable countries and the people who are most affected. So, wherever my career takes me, I’m hoping to continue that thread.

It is a very dynamic field as well- in terms of the different career paths you could take.

Yes, I could go back into scientific research or academia or even work for the government. My supervisor and my supervisor’s supervisor both have PhDs in science. A lot of schools now allow you to pursue a part-time PhD while actively working in the climate policy field. This field is very open and in some ways, that’s liberating but it can be confusing or intimidating because there isn’t a play by play available to tell you what your next steps should be.

Now let’s talk about what it’s like to be a woman of color in STEM. Do you feel you have equal opportunities compared to your male counterparts? How has being a woman in science impacted your career?

I think it’s really difficult being a woman of color in STEM in the US because you not only face the gender issues but you’re also facing racial discrimination along the way. The biggest thing I struggle with is the sense of belonging, or the impostor syndrome that comes with getting into spaces that are dominated by either men or white people. In the environmental field, at least in the US, the gender balance is okay at the junior staff level or even the manager level. But the higher you go into leadership positions, the fewer women- and even fewer women of color- you see. If you don’t see anyone who looks like you, it in turn becomes difficult to imagine yourself in those positions.

In my field, so much of our work happens through conversations or in meetings. If the men or white people are taking up the majority of the conversation, it can be really hard to make space for yourself.

What would you wish would change in your field to make it more inclusive for women of color?

Some of my mentors and supervisors are doing really great things that I’d like to highlight. They are making sure that the women and people of color on their staff have professional development opportunities and making space for everyone to speak up in meetings and voice their opinions. I really like that for events where we’re hosting experts, the people at CAP ensure that there’s gender diversity in the panel and that the panel is not all white. It helps with representation a lot. It also spurs people to consider the diversity issues in the field and why it’s so hard to build a diverse expert panel, especially consisting of people at top leadership levels. People in positions of power sit in a system that benefits them. They need to make sure it benefits everyone in the same way.

Do you feel like your work is demanding? How do you take care of yourself on the daily?

It is definitely demanding. Anyone who works in DC feels this sense of hustling, putting in the hours and making sure everything goes right. The way I take care of myself is by setting boundaries and finding time to do what I really love. Whether that’s playing video games or reading fantasy books and other things that are not directly related to my work. Working in policy, you can spend so much of your life reading the news or being on social media and getting outraged. I feel that I have to draw a clear line- I sit in the politics every day and therefore, I don’t need to sit in the politics outside of my work. It protects me from feeling really drained.

When you’re not working, where can we find you?

I’m probably on my couch reading or I like doing Friday night dinners at my local Thai restaurant.

Rapid Fire Round

What is the first thing that comes to your mind when I say ‘wildfire’?

Danger

If you were a plant or an animal, what would you be? And why?

If I could be a plant, I would be a pothos because I’m quite persistent.

What are two non-essential items that you’d want with you if you were shipwrecked on a deserted island?

I would want a fuzzy blanket and a journal. I would take it as a vacation!

Photos courtesy of Cassidy Childs (unless specified otherwise).

Leave a Reply