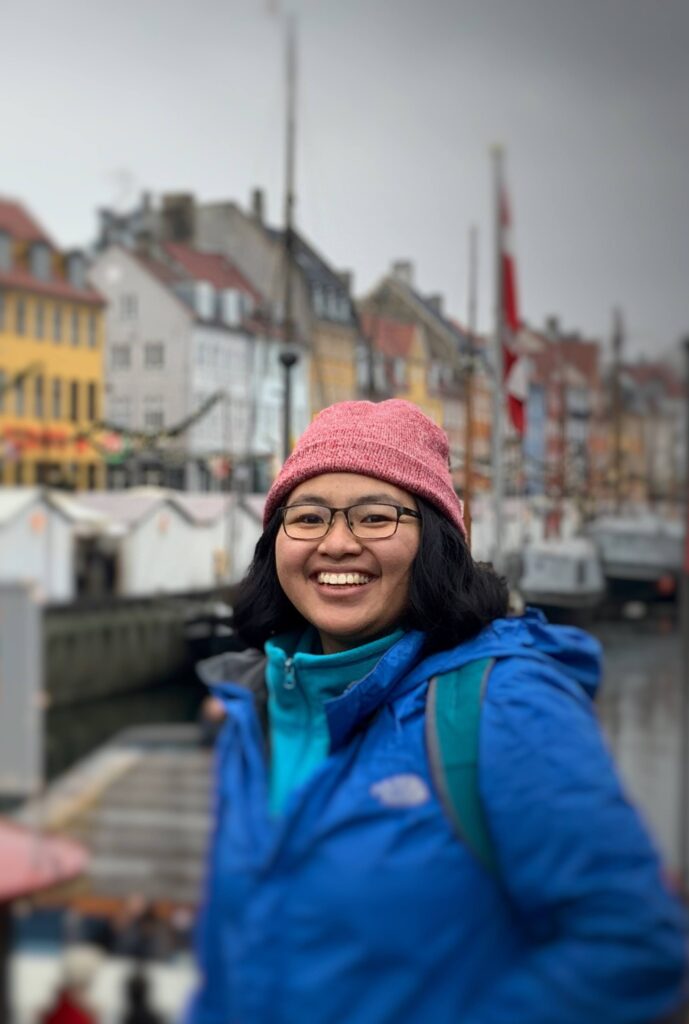

Iris Bea Ramiro

Bea grew up in the island province of Bohol in the Philippines. She has been surrounded by nature all her life which led to her interest in natural products, initially from plants and now from venomous marine gastropods.

She discovered a hormone-like peptide from slow-hunting cone snails, which has biomedical applications. She loves sharing her insights into the fascinating world of cone snails through science education and outreach projects. Having recently finished her PhD, she is continuing her research at Helena Safavi’s lab at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

When she is out of the lab, Bea is a photography enthusiast who enjoys traveling and exploring the outdoors.

Let’s start by talking a bit about your childhood and where you grew up.

I grew up in Bohol, which is an island province in the Philippines. I have a younger brother, and, like any typical Filipino family, we grew up living very close to our aunts and uncles. So even if it was just the two of us, my brother and I always played with our cousins because they lived nearby. Both my parents worked in a hospital in Bohol. We lived near their workplace initially and then moved close to the beach to help heal my brother’s asthma. I remember long walks by the beach so he could take in the sea breeze. It really improved his condition. Because we lived a bit far from the city, I had to travel a couple of hours or more each day to go to school and come back home.

I went to elementary school in Tagbilaran and to Silliman University in Dumaguete for my high school. So, I moved away from home at a young age.

While you were growing up, were there any subjects that you loved or hated in school?

Because my parents worked in a hospital, I was surrounded by people in the medical field. I was really interested in science, and also social studies and history- mostly because my parents and grandparents were very into talking about history. Our conversations at home or when we went to play in our grandparents’ garden would revolve around Filipino culture and history.

Was there one person, or a group of people, who influenced your choice of this career path?

Being in the medical profession themselves, I think my parents might’ve wanted me to be a doctor, which most of my cousins are. Our family gave us opportunities, through books and conversations, to explore scientific topics and ideas. My cousins and I played with fake blood that we made from bougainvillea leaves to fool our friends. My grandma liked collecting beautiful shells and other objects from the seashore. Just growing up with all that nature and exploration got me pretty interested in pursuing a STEM related course for my bachelor’s degree.

So, my family definitely ignited my interest in science. I gravitated towards the field of research that I’m currently in because of a talk I attended by Dr. Baldomero Olivera– who is a renowned cone snail venom researcher- when I was at the University of the Philippines, Diliman during my undergraduate studies. He talked about cone snails* and when he showed us videos of the snails hunting prey, I was pretty amazed. That’s what got me excited about cone snail research.

*Cone snails comprise over 900 species of highly venomous marine snails found in warm tropical seas and oceans all over the world. All cone snails are carnivorous, venomous and capable of stinging. They use a modified feeding structure that is shaped like a harpoon and a venom gland to attack and paralyze their prey before swallowing it. Learn more about their hunting strategies and venom here.

And how is it that you arrived at your chosen field of specialization, studying conotoxins within cone snail research?

I was studying chemistry at university. Natural products are a big research field in the Philippines and within our department. Herbal medicines are used a lot in the Philippines. So, I was interested in natural products and curious about what compounds in plants might make them effective remedies for certain conditions. I wanted to test whether these herbal treatments were just old tales or if there was concrete evidence that could be backed by science, to support their efficacy. So that’s how I started studying plant natural products for my undergrad thesis. Later this interest in natural products took me to conotoxins.

Which plants did you working on for your Bachelor’s thesis?

I worked on the sacred garlic pear, Crateva religiosa. Its local name is Balai Lamok. If you go to the University of the Philippines-Diliman campus, you’ll notice a lot of greenery there, including Balai Lamok trees. Traditional medicine claims that the tree has analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties and my thesis revolved around testing extracts from the leaves of the tree and isolating active compounds from them.

When did you transition to studying snails after that?

I always thought of natural products as materials, ingredients or extracts derived from plants. Attending Dr. Olivera’s talk really changed my mindset. Natural products from animals are very under-explored in the Philippines, especially marine natural products. I worked at the Marine Science Institute at the University of the Philippines for a long time and that’s when I became deeply involved in this work. It was similar to what I was interested in doing in plants- isolating active compounds from different plant parts- but now I got to study these fascinating venomous animals.

Were there any courses during your undergrad that you enjoyed a lot or any that came in particularly handy during your PhD?

I took up a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry. We had plenty of compulsory courses such as mathematics, physics, chemistry and biology. All the basic sciences. My university didn’t offer any course focused exclusively on marine biology, but you could take electives in general marine sciences, which were hard to get into but so much fun.

The non-science subjects I really loved were history, psychology, art studies and linguistics.

What came after you finished college?

Initially, I was exploring various career options, including industry-related roles, which are common for chemistry graduates in the Philippines. I had gained practical experience in analytical chemistry techniques and quality control during my on-the-job-training at a pharmaceutical company, but I found it somewhat uninteresting. I was more drawn to a career in scientific research, which I had really enjoyed while working on my Bachelor’s thesis.

So my passion for research took me on a different path and I began searching for research assistantship positions within the university after my graduation. I still had Dr. Olivera’s talk in the back of my mind, and it was during this time that I came across an intriguing opportunity at the Marine Science Institute, which involved studying marine snails, specifically turrid snails. These snails aren’t as well-known but they’re also venomous, so I like to think of them as the little cousins of cone snails.

This work allowed me to learn techniques in isolating bioactive components from marine snails. However, the smaller turrid snails made it challenging to obtain enough venom tissues to work with. I switched to cone snails, choosing the lesser studied deep-water cone snail, Conus rolani, which formed the basis for my Master’s project. It involved screening cone snail venom using various assay platforms and finally characterizing a bioactive peptide. Fast forward to my PhD at the Safavi Lab, I’ve focused on this bioactive venom peptide that I isolated and my research evolved to become more specialized and targeted.

Could you tell us more about your doctoral research?

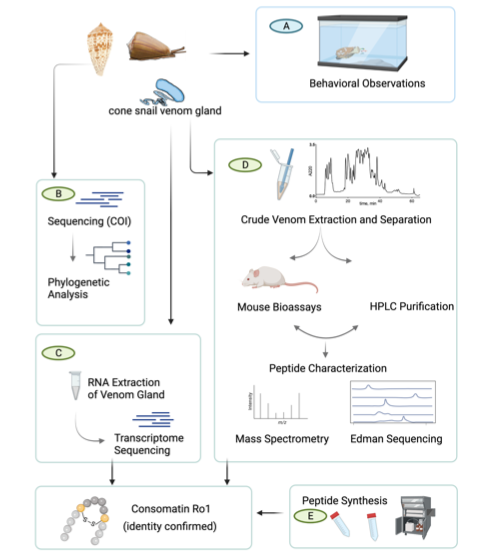

My doctoral research built upon my previous work during my master’s degree, focusing on the isolation of bioactive components from marine snails. In my master’s project, I successfully isolated these bioactive components, which were primarily peptides. At that point, we had an idea of their functions based on their peptide sequences, but it was somewhat limited.

A pivotal moment in my research journey was the opportunity to collaborate closely with Dr. Olivera and other experts in his lab. This collaboration led me to my PhD supervisor, Dr. Helena Safavi, who had a project aligned with one of the peptides I had discovered.

My PhD research primarily focused on hormone-like peptides found in a specific group of cone snails. The peptide I discovered is similar to the vertebrate hormone, somatostatin, which is involved in various physiological functions. My work involved identifying the receptor targets of this somatostatin-like venom peptide and exploring its applications, particularly in the context of pain and inflammation.

The research process involved collecting these snails with proper permits and dissecting their venom glands, where the bioactive components are concentrated. We then froze these components with liquid nitrogen to preserve their integrity. In the lab, we purified and separated these components using chromatography and tested them in various assays to identify biologically active peptides.

My doctoral research expands our understanding of cone snails, their venom, and the potential applications of the bioactive peptides they contain. It’s an exciting journey that bridges marine science with the biomedical perspectives. What’s interesting is that the venom glands contain a vast cocktail of compounds and we’re finding is that every single peptide or every single toxin within this compound library has a different activity. So we’re constantly discovering many new things.

Is this cocktail of multiple bioactive compounds found within cone snail venom one of the reasons it’s been difficult to produce any anti-venoms for conotoxins?

Perhaps but it could also be because deaths caused by cone snail venom aren’t very common or not reported. I only know of one species, Conus geographus or the geographer cone, whose venom is potent enough to be deadly to humans.

So, getting stung by a cone snail might be painful and dangerous but isn’t usually deadly for humans…

Yes. How the toxin becomes dangerous is that it can cause breathing issues* in humans. Nowadays, this can be handled in hospitals with access to oxygen tanks and assisted respiration.

Having said that, Conus geographus is a common species in the shallow waters where our group goes on collection trips in the Philippines. So, we need to be very careful and keep the fisherman working with us well informed of all the safety protocols.

*Cone snail venom contains various peptide-based neurotoxic compounds known as conotoxins. Conotoxins have many different mechanisms of action and they each target a specific nerve channel or receptor, most of which haven’t been determined yet. Cone snail stings can cause intense, localized pain, swelling, numbness and tingling in humans. Severe cases can result in muscle paralysis and respiratory failure so medical attention must be sought immediately in case of a sting.

Congratulations again on having finished your PhD recently! What is it that you find most exciting as you continue working as a researcher at the Safavi lab?

What’s most exciting for me is to be able to continue working on the new questions and research directions my PhD work has generated. I’m getting to use newer tools to explore these questions and also expand to other study organisms. For instance, we’re now looking for somatostatin analogs in the venom of fish hunting cone snails like Conus geographus.

What are your plans for the future?

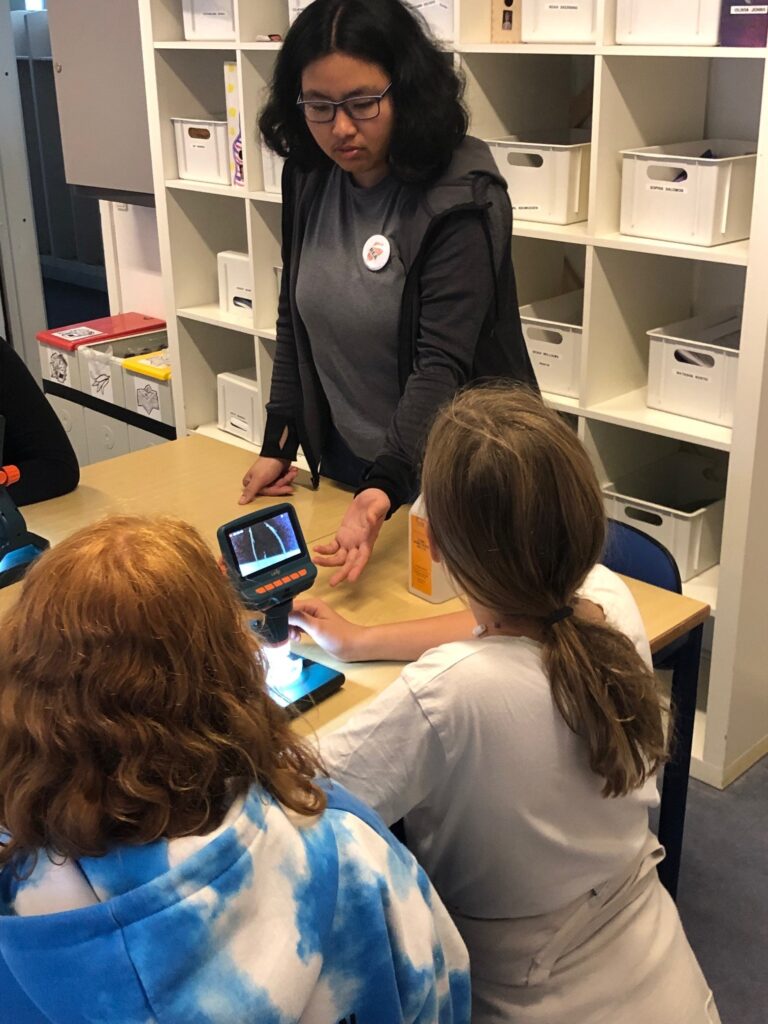

I would really like to continue doing research focused on venoms from cone snails. The possibility of finding new things and making novel discoveries is really fun for me. I’ve been involved in science education and outreach projects that I’d like to continue working on. Of course, this can be tricky especially if you’re working with younger kids in Denmark because you need to speak Danish really well to distill complex concepts into easy-to-understand ideas. So, it’s a work in progress.

Now let’s talk about what it’s like to be a woman of color in STEM. Pursuing a career in academia comes with its unique set of challenges. Do you feel you have equal opportunities compared to your male counterparts? How has being a woman in science impacted your scientific career?

I’ve always had strong women role models to look up to. My supervisor is a woman of color here in Denmark. I’m learning a lot from her experiences balancing her work and family life. I’m not sure I’ve considered my circumstances in the light of my being a woman in science too much. However, I remember coming up against this issue recently while looking for examiners for my PhD assessment committee. The university recommended that I have at least one female examiner on the panel, but we had a lot of trouble finding anyone suitable. This triggered a conversation around representation and diversity in our lab group.

For me personally, I’d say being a Filipino here in Europe adds another layer to my experiences. I feel that being a person of color who isn’t in their home country governs a large part of the challenges I face at the moment. Some of these, like struggling with a different language or bureaucratic process, are an integral part of moving to a new place. Others have more to do to specifically with my being a scientist. For example, opportunities for funding research are limited for me compared to my European counterparts.

What would you wish would change in your field to make it more inclusive for people of color?

I think funding opportunities that are catered towards people of color are not as common in Europe so that could be something that might help make my field more inclusive. Making the selection process for grants and jobs more transparent so that candidates know what goes on behind the scenes could help too.

Academic careers can be very demanding. How do you take care of yourself on the daily?

I think it’s really nice that Denmark is very bicycle friendly. I bike to the lab every day. Being outside and in nature is something that allows me to disconnect. I really enjoy being around kids so I also play with my friends’ kids or volunteer for outreach and education projects focused on making science fun for children.

When you’re not working, where can we find you?

If I’m not relaxing at home, then I’d probably be traveling and exploring Denmark and other parts of Europe. Probably taking lots of photos.

Rapid Fire Round

What is the first thing that comes to your mind when I say ‘snail’?

Conical

If you were a plant or an animal, what would you be? And why?

I’m sure you can sense a theme emerging, but I’d say a snail because I’m pretty shy. So just like a snail, I often hide in my shell and need to be tickled to emerge. But hopefully not to sting anyone!

What are two non-essential items that you’d want with you if you were shipwrecked on a deserted island?

Maybe a camera for fun. And perhaps a journal… I already said camera and now I won’t have anything to write with. If you allow me three items, I’d say a writing instrument. Otherwise, I’ll need to be creative about making one for myself on the island.

Photos courtesy of Iris Bea Ramiro (unless specified otherwise).

Leave a Reply