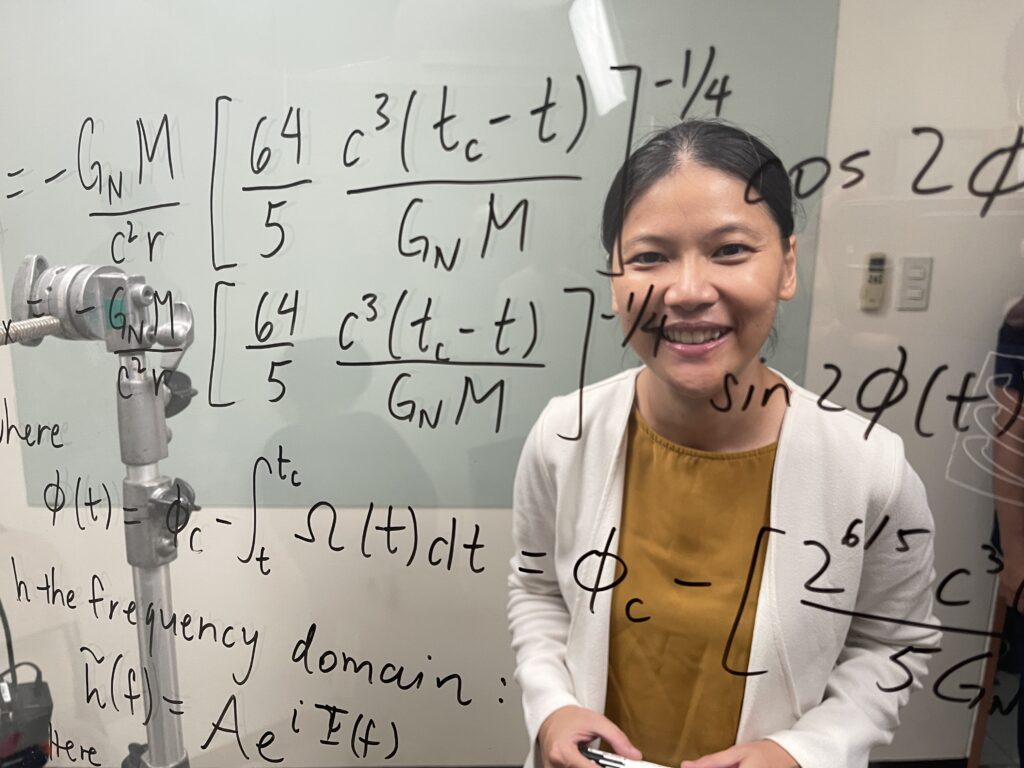

Reinabelle Reyes

Reinabelle Reyes, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor at the National Institute of Physics (NIP) in UP Diliman, where she heads the Data and Computation (D&C) Research Group. She serves as a data science consultant for UNDP Philippines, Z-Lift Solutions, Inc. and Citizen’s Budget Tracker. She is also co-founder of Pinoy Scientists and adviser of SEDSPH (Student for the Exploration and Development of Space – Philippines Chapter).

Learn more about Reina’s STEM journey through her conversation with our Education and Research Fellow, Swastika Issar:

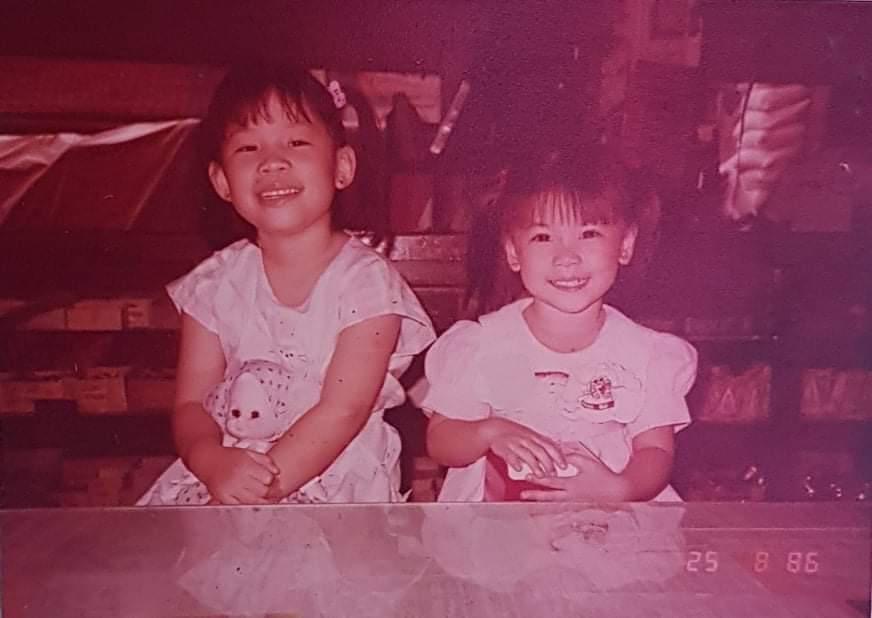

Let’s go back to the beginning, could you paint a picture of your childhood for us? Did you have any siblings? What was a typical day like for you when you were growing up?

I grew up in a town called San Juan in, in Metro Manila, which is the capital region of the Philippines. It was a very urban environment. I’m second-generation Filipino Chinese. Three of my four grandparents immigrated to the Philippines from China. Many people from my parents’ generation in the Filipino Chinese community were entrepreneurs and ran their own businesses. My family ran a construction supply shop that sold everything you’d need to build and paint a house. Typically, families like ours would live on the top floor of the shop. So, my siblings and I grew up living on top of a bustling hardware shop in one of the busiest parts of town opposite the tricycle station and the wet market of San Juan. I spent a lot of my time as a child looking out from the window of my bedroom, just watching people come and go. I’d wonder what they were thinking and what their lives were like. The biggest contrast for me when I moved abroad for my studies was how quiet everything was. I used to have a hard time sleeping when it got so quiet.

Coming back to my childhood, my parents ran the shop together and they had three daughters. I’m the middle child. Me and my sisters would sometimes help our parents run the shop. We would manage the cash till or write cheques for our suppliers. We learnt to do quick mental math- addition and subtraction without using a calculator- so we could return change to our customers quickly. A lot of what we did were exercises in school too, but we learnt them in a more practical manner. Along with occasionally helping at the store, our childhood revolved around going to school, learning and playing with our friends.

Was education considered important in your family and did both your sisters go for higher education as well?

My mother was one of thirteen siblings. At that time in Chinese Filipino culture, the women didn’t really need to finish school. They used to get married off at a young age. My mother insisted on going to college. Only two out of thirteen siblings wound up going and my mother was the first in her family to finish college.

So, I’d say it wasn’t unusual that my sisters and I also wound up getting a good education. I was the only one who went into science and to graduate school. My older sister has a degree in business and the younger one studied industrial engineering.

While you were growing up, were there any subjects that you loved or hated in school?

Math was my favorite subject. I was exposed to it at home early on. In school, I really loved it because it wasn’t subjective. When you’re solving a problem, you just need to follow the right steps to arrive at the correct answer. You don’t necessarily need the teacher to tell you that you’re right. This idea that if I got that answer, I’d get a perfect score appealed to me a lot.

In high school, I was introduced to physics. And physics became my new favorite subject. There’s a lot of math involved when you’re solving problems in physics, but it has real world applications. I hadn’t really thought at that time that I’d like to become a physicist. I’d just liked the subject more than chemistry or biology.

Was there one person, or a group of people, who influenced your choice of this career path?

I’d say all of my teachers through high school and middle school have been the most impactful. Most of our family friends and relatives were also in business. So, the closest anyone in our circle would be to a physicist is probably an engineer but I didn’t really know anyone who was an academic. I had found out about the Philippine Science High School (PSHS) and told my parents that I wanted to try to study there. My parents didn’t know about the school because people from the Filipino Chinese community tended to send their kids to a Filipino Chinese school. Mostly because everyone in their social group was doing the same thing. So, it was a big deal that PSHS was not a Chinese school. There aren’t many parents in our community who would’ve been willing to let their kids go there. Ultimately this was possible only because my parents were open minded enough to let me pursue my interest in science by going to PSHS.

It all really began for me when I cleared the competitive exam and began my first day at PSHS, which is a magnet school for students interested in science and engineering. The government provides resources to promote STEM talent and tuition is free. We were really lucky to get to interact with researchers. Many of our teachers were also pursuing graduate school at the University of the Philippines or Ateneo de Manila University. It wasn’t just our teachers. This is the first time I got to meet kids my own age who enjoyed math and science and were really good at it. And this was really inspiring for me too.

Was there any particular moment in your life when you felt a pull towards becoming a scientist in your field of specialization?

While I was at PSHS, I was a part of the team that represented our school at the Philippine Physics Olympiad which is a competition where you get to solve advanced physics problems. Me and another student were in our third years, but the rest of our team were seniors in their fourth year of high school. I was at a stage in life where I was trying to figure what’s next for me. I remember thinking going into the Olympiad that if I do well, I’d take it as an affirmation that this was the right career path for me. I wound up placing third in the nationals and got the sign that I needed to pursue a career in physics!

For any young students who are thinking of a career in physics and machine learning, what kind of courses did you study at university as an undergrad?

I got my bachelor’s degree in physics from Ateneo de Manila University. There was a big emphasis at Ateneo on holistic education. So, it wasn’t just all about your major. Along with physics, we also took a lot of philosophy, theology and language studies courses. I really enjoyed that well rounded education. I learned how to write well, how to read philosophy and appreciate the humanities. At the same time, I really wanted to specialize in physics. There was a hunger in me that motivated me to pursue graduate school. We had a group of 5 friends in college and we started something called ‘The Kindergarten Club’. We discussed physics papers and problems on top of what was required of us in school because we really enjoyed learning.

At that time though, my idea of what I wanted to specialize in was very naive. I wasn’t really exposed to all the research happening around the world. When I was in high school, I’d read many popular physics books on the theory of everything, string theory and the fundamental particles. So, I was really interested in particle physics* because this was the most fundamental you could get.

*Particle physics or high-energy physics is a branch of physics that deals with fundamental particles and forces that constitute matter and radiation.

What came after your undergrad studies?

I ended up pursuing a diploma in high energy physics at the International Center for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, Italy. It is an ideal bridging program for students from developing countries who are interested in graduate studies abroad. If you’re selected for a scholarship, you get a full stipend and living allowance for the entire time you’re there. It really opened many opportunities for higher education for me.

Being at ICTP felt like being a part of the United Nations to me! There were students from Brazil, Palestine, Trinidad & Tobago- many people from developing countries and also around Europe who all shared this love for physics. I felt a lot of kinship with our cohort.

Were there an equal number of male and female students?

In my class of 20 students, there were four women and then the rest were men. I’d say most of the programs had a majority of male students, which is not uncommon for our field in general.

And you went on to pursue a PhD in the US thereafter?

During my diploma at ICTP, I’d also become interested in cosmology. Along with our classes, we were required to work on a small research project with an advisor. I approached Prof. Uros Seljak, who was a cosmologist at ICTP, and my project with him was focused on theoretical cosmology. I was advised by a mentor to consider pursuing a PhD in astrophysics. In my grad school application essays, I talked about wanting to pursue research at the intersection of particle physics and cosmology. I applied to several different graduate schools in the US and was accepted to the astrophysics program at Princeton.

How was your grad school experience?

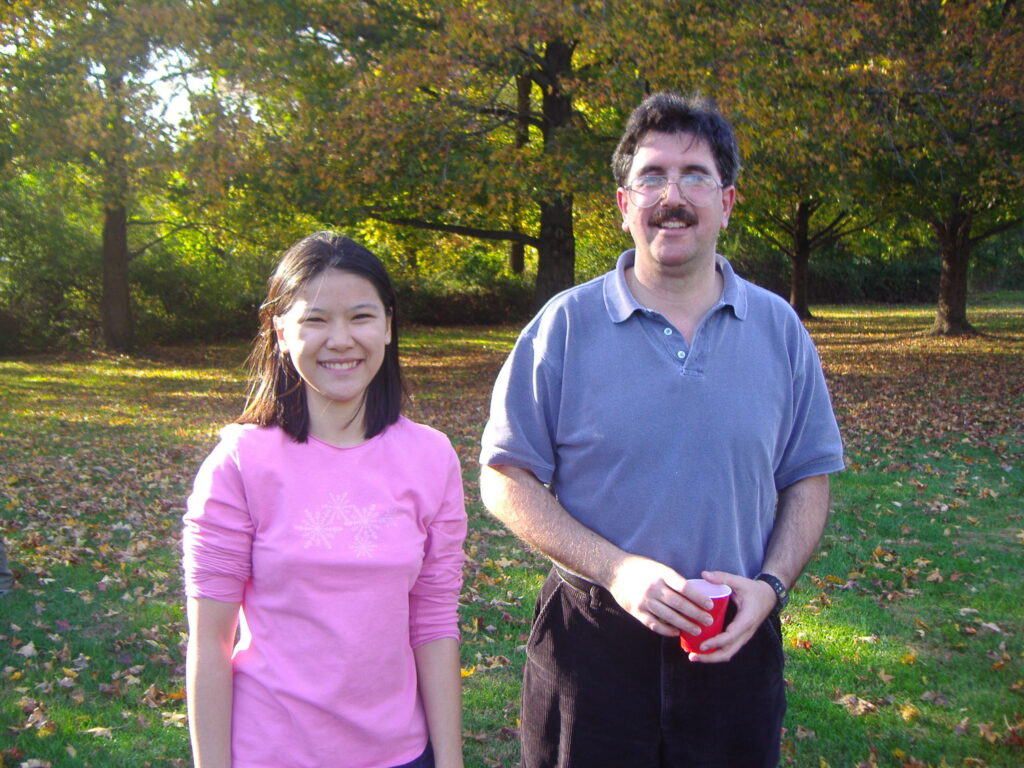

My primary training before grad school was in theoretical physics. At Princeton, I got to learn and absorb this whole world of astrophysics and ended up becoming an observational astrophysicist. We dealt with large data sets and my work became very data driven. Every semester for the first couple of years, we did a new project with one of the professors at the department. Being new to observational astrophysics, I wanted to work with someone who was friendly and patient in explaining concepts. One semester I worked with Prof. Michael Strauss. The project was an extension of his former student Nadia Zakamska’s PhD project. At that time, she was a postdoc at the Institute of Advanced Studies (IAS), also located in Princeton. She had done the foundational work of building the first catalog of Type 2 quasars*. Eventually, we got to publish this work together.

*Called the ‘brightest objects of the universe’, quasars are distant starlike heavenly objects that produce tremendous amounts of energy. They give off very strong blue & ultraviolet light and powerful radio waves. A quasar is always found near a supermassive black hole.

Most of the professors in our department were men but a larger cohort of the postdocs were women. Looking back, supportive postdocs played a really big part in my growth as a scientist. Often there can be this culture of “sink or swim” in competitive labs where the student is left to their own devices. But that’s not at all what I found. My senior colleagues made me feel like a part of the team and almost made it hard for me to fail.

What was your PhD on?

My PhD was in the field of gravitational lensing. I did my thesis in Prof. Jim Gunn’s lab. I worked with his postdoc Rachel Mandelbaum, who did her PhD with Uros and was a postdoc at IAS at that time. Gravitational lensing stems from the fact that starlight is bent when it goes around the sun or galaxies. On a cosmological scale, the light from faraway galaxies gets distorted by big galaxies or clusters of galaxies along the line of sight. My thesis was on measuring the effects of gravitational lensing on the shapes of galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, which was what Rachel worked on for her PhD thesis. We used gravitational lensing to empirically test Einstein’s theory of general relativity. This got us a lot of press and a Nature paper!

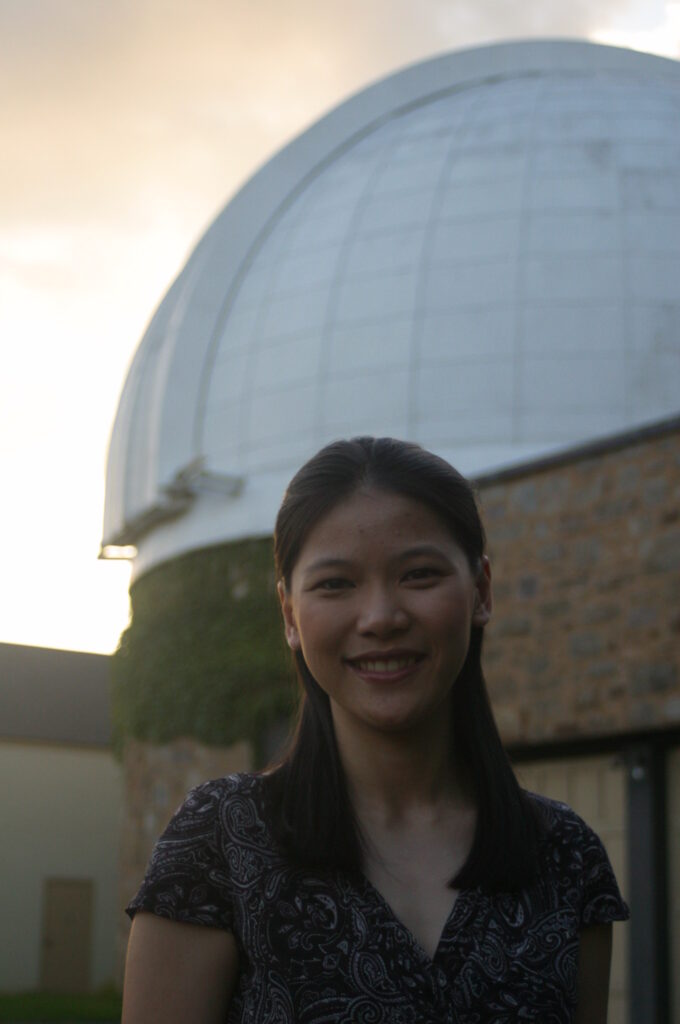

And what came after your PhD?

After my PhD I followed the usual path of applying for postdoc positions. I had considered the question of coming back to the Philippines right away but decided to do at least one postdoc in the US.

Astronomy is a relatively small community. So basically, you apply to places where they do science similar to what you’re doing. You go meet people, give talks about the findings of your research. And then decide from the offers you receive what you find most exciting. I ended up at the Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics at the University of Chicago. They’re involved with the Dark Energy Survey, which is the next generation of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. I’d been working on data from the Sloan Survey earlier. The Dark Energy Survey has images of millions of galaxies that are much further away and formed earlier. So, I spent a good few years studying gravitational lensing in galaxies across the universe.

Was there a big Filipino community that you could connect with at the University?

This is something that was on my mind a lot. And it prompted me to start Pinoy Scientists so I could build connections with the Filipino science community, both in the diaspora- because Filipinos have moved to many different places in the world- and with scientists back at home. I invited everyone I knew, be it former professors or former classmates and started sharing their profiles on a Tumblr blog.

Is this initiative still running?

Yes, and it is still evolving! When I started it was just a personal project back in 2012. I followed this Tumblr blog called ‘Looks Like Science’. I don’t know if they still exist, but their idea was to feature diverse scientists from many different walks of life and fields of research. It challenged the stereotypical white man in a lab coat idea of a scientist. Inspired by that, I decided to start a blog for Filipino scientists.

“Pinoy” is a colloquial term for Filipinos and the two can be used interchangeably. Our tagline was “Yes, we exist”. I came up with a simple questionnaire. I asked the featured scientists to send me a write up about their work, what they do for fun and a picture of themselves. The content wasn’t just focused on the serious side of science, but also showed that scientists are relatable people with lives and hobbies outside of science. This was the initial idea, and this experience really enriched me.

Of course, it was just me doing this on the side at first. It started with the people I knew and then it became the people they knew. I added a Facebook page. Pinoy Scientists grew from there to a much bigger network. Many people helped in this evolution. Kami Navarro, our current Managing Director for Operations and Communications- who has a Master’s in science communication- approached me in 2019 with the idea of starting an Instagram page. Our featured scientists take over the page for a day and interact directly with our audience. A lot of our older audience is on Facebook, so we cross post across different media platforms.

We have another partner, our Managing Director for Technology, Gerson Lacdao who is a web developer. We’re all volunteering our time towards this project and are joined by eleven more interns. We also launched our website this year! The growth of Pinoy Scientists has been very organic, our volunteers see the value of our platforms and want to help us grow. This has been very affirming for us.

What’s next for Pinoy Scientists?

We’re actively establishing partnerships with organizations with shared advocacies. Specifically, we are pursuing joint projects with the Philippine-American Association of Scientists and Engineers (PAASE) and WeSolve Foundation to strengthen our programs and better serve our community.

Exciting times ahead! It’s wonderful that this initiative continued to grow when you came back to the Philippines. When did you return?

The story goes that I decided to come back home right after my postdoc. I didn’t apply to an advertisement. I spoke to my alma mater at Ateneo de Manila University, and they were happy to have me join them as an Assistant Professor in 2014.

What prompted this decision to return to the Philippines at this stage in your career?

29-year-old Reina had noticed that many scientists returned to the Philippines after they retired. So, they spent most of their careers abroad, either in academia or in industry. And they live with this urge to give back and contribute to their home country all their lives. I wanted to move to the Philippines as a young scientist so I could spend many productive years here contributing actively to research.

Did you move to the University of the Philippines recently?

I started in 2020. Before that, I also worked in industry roles both as an independent consultant and as a data scientist in many different sectors ranging from telecommunications to e-commerce platforms and even healthcare.

Could you give us a summary of your work and the research being carried out in your group?

In my current position at UP Diliman, I teach and run my own research group called the Data and Computation Group, D&C for short. Our research primarily spans two major research areas. One is data-driven astrophysics and the other is what I like to call ‘data for social good’. The second area is broader. We use machine learning to study data sets for studying trends in education, for detecting fake news or for any other project my students care about. I’m happy to see that the younger generation is very socially aware, and they want their science to impact society.

The first area involves using machine learning for applications in astrophysics. One of my graduate students is working on time series forecasting of gravitational waves, using deep learning. So, technology allows us to predict merger events- where two compact objects such as neutron stars merge- about 10 seconds before the event actually occurs. The application is that the Gravitational Wave Observatory can then alert the other telescopes to observe that object in space. You could get different wavelengths of observation such as radio and optical. This is called multi messenger astronomy, which is an emerging field where you get signals from different sources that allows you to build spectrograms of events occurring in our Universe.

What is it that you’re most excited about your current position at UP Diliman?

I’d say the research I’m doing with my students and collaborators. I’m only just starting to collaborate with my fellow faculty. And the possibilities excite me.

I always tell my students: “This is your thesis topic and you’re going to be working on it for a substantial amount of time. You might as well choose something that you actually care about and are really interested in.” I like to give them the freedom to pick a topic and then we look at potential projects together. For instance, one of my students composes music. She’s a foley artist who creates ambient sounds for video games and movies. She wanted to do her thesis on sound design. She looked at related literature and found cellular automata sound synthesis. This entire process from conception to developing the algorithms that create sound which is then turned into audio, it’s just such a joy. And even sweeter because it’s full of challenges. Helping the students troubleshoot the issues they face is also something I really enjoy. Now the student is ready to defend her thesis. This whole journey that I get to go on with my students brings me a lot of happiness.

What are your plans for the future?

Our lab is at a nascent stage, and I’ve got the chance to work on many different projects with my students since we started out. The next step for us is to build on each for these projects so we can put together complete stories for publication in peer reviewed journals. For instance, I have an undergrad who finished last year and has now joined us for his Master’s degree. So, this gives us more time to build on the work and get it ready for publication. Unlike in industry, where projects are three to six months long, research projects take time to come together. This is what I’m going to be focused on for the next few years.

Do you feel, throughout your journey, that you have had equal opportunities compared to your male counterparts? How do you think being a woman has impacted your scientific career?

Looking back, I think it did influence my specialization. While I was at Princeton, I was interested in pursuing particle physics, which is fundamental theoretical physics. While looking for potential advisors to do my project with, I approached a professor in the Physics Department who was a theoretical cosmologist. He was welcoming and included me in some group meetings with his students. And he told me that I could attend some of his classes too. What I remember when I sat in those classes is that I suddenly realized that I was the only woman there. It wasn’t a very small group, there were about 30-35 people in each class. I think this is partly why I didn’t continue. Some male dominated fields aren’t very welcoming towards women.

I ended up working with other groups focused on observational astrophysics. I received a lot of support and good mentoring from the female postdocs in the lab. I think that made a big difference to my career, so I don’t regret making that choice in any way.

What would you wish would change in your field to make it more inclusive for women?

Having more women professors in senior positions can make a difference. The dominant culture in academia from the language used to drinking & socializing to the social mores all still tend to favor men.

Of course, it’s also generational. People from different generations think very differently from each other. I think having women guiding and supporting both younger women and men in their fields will help change perceptions and work culture.

We know that academic careers can be very demanding. How do you take care of yourself on the daily?

Or how I should be. My usual go-to is exercise but I’ve been falling behind on my workouts recently, so I’ve taken to yoga and jogging, which are less intense.

Meditation also helps a lot. I’m a serious practitioner of Zen and go on silent retreats with my Zen group. These retreats are always something that I look forward to.

When you’re not working, where can we find you?

On a bike trail or a basketball court.

Rapid Fire Round

What is the first thing that comes to your mind when I say ‘gravity’?

Black holes

If you were a plant or an animal, what would you be? And why?

A hedgehog because they’re cute.

What are two non-essential items that you’d want with you if you were shipwrecked on a deserted island?

Any book by Murakami and a basketball.

Photos courtesy of Reinabelle Reyes.

Leave a Reply