Janneli Lea A. Soria

Janneli Lea Soria is a geologist and science educator. She is committed to fostering a sense of wonder about the earth and engaging students in exploring and learning about earth processes. She obtained her Ph.D. degree and worked as a Research Fellow at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. She collaborates with other geologists, oceanographers, engineers, and social scientists in investigating coastal hazards such as storm surges, tsunamis, subsidence, and coastal erosion. In 2019, through the Balik Scientist Program of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), she developed learning modules, conducted various research activities and training workshops that build linkages among educational institutions, private organizations, and coastal communities in taking collective action on disaster risk management in the Philippines. Dr. Soria joined the Central Visayan Institute Foundation in Jagna, Bohol in August 2020. She is serving dual roles as the Director of the JAZC Marine Sciences Laboratory and the expert Earth Science and Research teacher for Senior High School (K11 and K12).

Learn more about Lea’s STEM journey through her conversation with our Education and Research Fellow, Swastika Issar:

Let’s go back in time, could you paint a picture of your childhood for us?

I grew up in a close-knit community in Isabela, that’s a province in Northern Luzon, the biggest island of the Philippines. We lived in a valley with these expansive plains of rice fields and big mountain ranges on both sides. I have two siblings, a brother and a sister and I’m the eldest of the lot. Growing up, we played outdoors a lot. We didn’t have a TV so our screen time was limited to visits to our neighbors.

When I was little, both my parents worked with the National Irrigation Administration. We had a few hectares of rice fields that us kids would visit from time to time with our dad. Every day before going to school, we would leave our cows and goats to pasture and then after school, we’d go collect them from the meadow.

During the time that I entered elementary school, my mom, who had a background in agricultural engineering, began pursuing her passion for education. She taught at a private school first, then took some educational units and cleared the licensure exam.

There was a point in my childhood when my dad was gearing up to travel overseas for work to better provide for our family. It was around then that one of the strongest typhoons of that time hit Luzon and forced us to move to a new home. This brought a lot of changes in our lives and our perspective. My father decided to continue working with the local government as an agricultural technician until he retired last year.

Tell us about your time as a student- were there any subjects you particularly loved or hated?

I’ve loved learning ever since I can remember. My mom and dad tell me that I was a naturally curious kid who was always exploring her surroundings. I’d even sneak out of the house when I was three years old and go to the neighborhood store.

As a kid, I didn’t like the way we were taught history in school, but I loved all my other subjects. In high school, I picked science. I think I gained an interest in it because of my Grade Four teacher, who was passionate about explaining things and making his students understand difficult concepts.

Both my parents had a background in agricultural sciences. My mother taught general science and chemistry in the same school where I studied. Growing up we had these two massive volumes of an encyclopedia that we would just browse for fun. I remember looking at pictures of the Grand Canyon and wanting to go there. I also grew up reading the Reader’s Digest. All this helped expose me to a lot of different kinds of knowledge.

Is there a person who you feel has been influential in you choosing your career path?

Oh, that’s an interesting story. Before going to college we had to choose three courses at the University of the Philippines. So I’d shortlisted chemistry and physics and was thinking about what else to pick. My dad suggested geology, which I hadn’t really heard much about before. He told me about this engineer from the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) who had come to install a seismometer in our town to monitor seismic activity after the 1990 earthquake in Luzon. My dad had been his guide. When I was in elementary and high school PHILVOCS was huge, because that’s when the Mount Pinatubo eruption occurred. Lahar episodes* still continued during the last year of my high school. I’d never heard of a geologist in our town and didn’t know what a geologist did but I decided to just go for it and picked geology as the second option for my undergrad studies. When I got to university, the chemistry course was already full. So I went with my second choice. I think I’m a geologist by accident but a very happy accident at that.

*A lahar (/ˈlɑːhɑːr/) refers to the violent flow of pyroclastic material, rocky debris and water from a volcano, typically along a river valley.

How did you arrive at your chosen field of specialization? Did you always want to work in disaster management?

After my Bachelors degree I went straight into a Masters. The mining industry and off-shore drilling jobs catered more to men. The mining industry was also down at the time. So most of our cohort went into academia, at least most of the women did. The first research topic that I was involved in after my undergrad was on natural hazards, in particular on coastal flooding in the delta complex along the northern coastline of the Manila Bay. I’ve always gone with what’s felt natural and authentic to me in my career. My field allows a strong connection of science with the community. It can be frustrating to work with policymakers but it’s so different when you work directly with communities. It makes my science more relatable. Aside from my Master’s project, I also worked with Quick Response Teams on hazards assessment between 2005 and 2006, when there were two big landslides in the Philippines. I was a part of search and rescue missions, which most scientists don’t really experience. We’re not trained to be first responders. My experience exposed me to the reality of natural disasters and the impact of hazard assessment in preparedness towards avoiding large-scale calamities.

I did my PhD from the Asian School of the Environment at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. I enjoyed it very much, made a lot of friends. We had professors from many different backgrounds working on Earth systems, ecology, climate change and natural hazards such as earthquakes and volcanoes. During my Masters I’d already moved towards studying the applications of disaster assessment such as flooding and land subsidence. The skills that I developed in sedimentology: looking at layers of sediments, and telling the history of an area, for example, how the delta in Manila evolved, were essential skills during my PhD. I presented the results from my Masters thesis in a conference in Australia, where I met my supervisor. I was recruited to work on storm surges* and tsunamis for my PhD a couple of years later.

*A storm surge is a tsunami-like phenomenon of rising water or coastal flooding commonly associated with low-pressure weather systems, such as a cyclone.

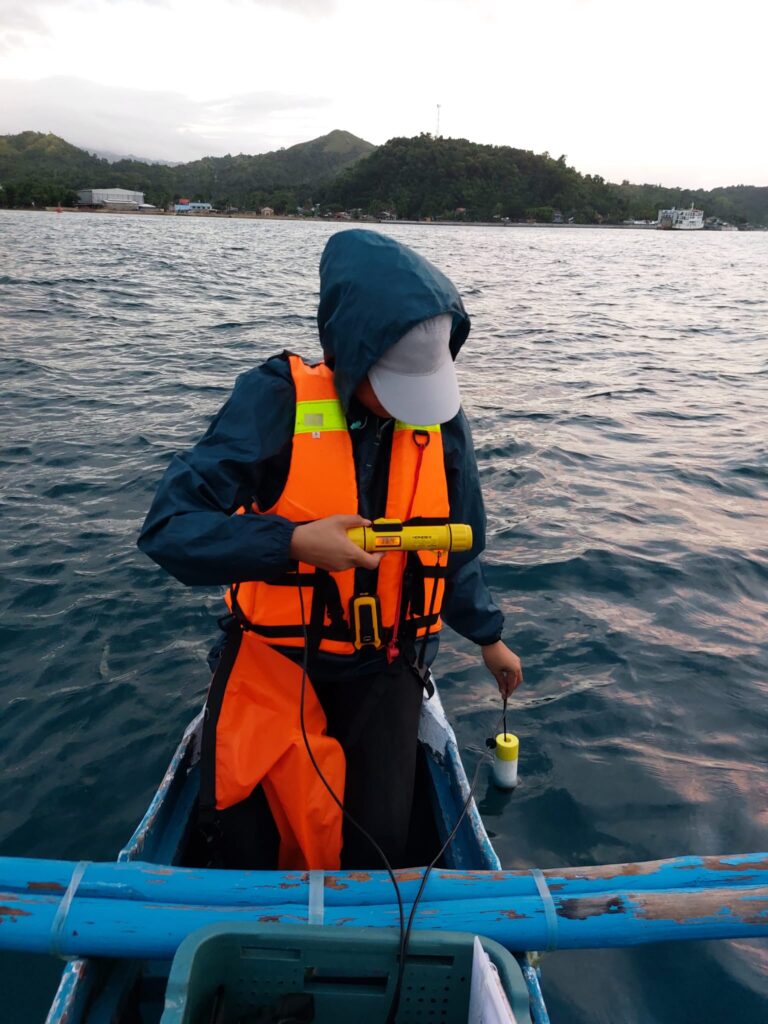

I realized that while sediments had been studied in the context of earthquakes, nobody had worked on the occurrence of storm surges in the Philippines using sedimentology before. We had historical records, of course, but extending our understanding beyond the historical or instrumental record has not been done. The sedimentary records of past events need to be compared to a modern-day example so you have a template for what sedimentary signatures might look like. I started my PhD in 2011. The last storm surge that had happened in the Philippines was in 2007. We used two different methods to study the sediments or geomorphology in the regions. Firstly, by directly drilling the soil and studying the composition of the sediments and secondly, using a ground penetrating radar (GPR). A GPR is a sort of a scanner and sediment analysis using a GPR can be thought of as doing an X-ray of the ground. How deep the radar penetrates depends on the frequency that you use. The lower the frequency, the deeper the record of sentiments that you can see. However, if you want good resolution of the layers, you need to use a higher frequency. Storm surges show up in terrestrial sedimentary records because they bring oceanic sediments and foraminifera* into the land. Studying the assemblage of foraminifera shells, i.e, whether they came from the water or the ocean floor, can help us understand how powerful the storm surge was and the depth of oceanic sediments it dug out.

*Foraminifera (/fəˌræməˈnɪfərə/) are single-celled organisms, belonging to the clade of amoeboid protists. Their external shells are made up of many different materials and take on diverse forms. Most foraminifera are marine and are found living on the seafloor sediment and floating in the water column at various depths.

Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines in late 2013 and was one of the most powerful tropical cyclones ever recorded. I was in prime position to study signatures of Typhoons and storm surges in sedimentary records at the time.

Looking at the sediments helped me understand the dynamics of water flooding. I studied the depth at which sediments were disturbed in the sea. We interviewed people and measured the height of the waves and the direction of the flow using video recordings of the Typhoon. I worked with oceanographers who simulated or modeled the storm surge because we didn’t have an instrumental record at that time.

I got to learn many new skills during my PhD and, most importantly, work on something that impacted the lives of thousands of people in my country.

This must’ve been such a fun project with lots of fieldwork and interdisciplinary collaboration! What came after and how did it bring you to CVIF?

After my degree I decided to return home and take a sabbatical for about a year and a half before applying to the Balik Scientist Program of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST). This Program allows returning scientists to share their expertise in promoting scientific and economic development within the Philippines.

My host institution was the Marine Sciences Institute at the University of the Philippines, where I’d worked before leaving for my PhD. During my six months of engagement here, I helped groups at the Institute develop proposals for scientific research in my area of specialization. Another aspect of the Balik Scientist Program was outreach outside of the University of the Philippines, either to collaborate or to train personnel at other institutions. The Central Visayan Institute Foundation at Jagna, Bohol was on top of my list for places that could help me transition to a meaningful career in science education.

How did you become interested in education? Was it during your PhD or when you were growing up?

I didn’t really want to be a teacher growing up. During my PhD, we were required to take this module developed by the Pedagogical Department of the National Education Institute before we could take up a teaching assistantship. This course was an eye opener for me.

Our professor said that as teachers we are the facilitators of learning. The process of teaching need not be through long lectures. The idea was to facilitate the engagement of the class in learning activities in a learner centered setting. And I thought at that moment that Earth Sciences could be a great platform to introduce kids to science education in general, especially in the Philippines. Our country is so diverse in geology. Yet, we have few geologists. Because of active tectonics we have a lot of earthquakes and volcanoes. So geology is not an abstract concept for students. You can introduce concepts in physics through the climate and weather events like typhoons or chemistry through rock and minerals. This idea is what made me shift towards education. I remember telling my supervisor that if I don’t end up teaching in a university setting, I’d like teaching Earth Sciences to kids.

What’s the most exciting thing for you in your current position at CVIF?

I moved to CVIF, particularly because of the Dynamic Learning Program (DLP). It’s very difficult for me to transition to science education through the public education system because the same core curriculum is meant to be followed nation-wide and is very difficult to tweak. At CVIF, we still follow the Department of Education curriculum, but DLP allows learning materials to be developed that suit the needs of the students. What I particularly advocate is contextualizing concepts using local examples that students can relate to. For example, learning about local volcanoes here in Bohol. Many students can see Mount Hibok-Hibok on Camiguin Island from their windows at home. Why not teach them about the history of the Pacific Ring of Fire using this example? The freedom to develop learning activities using my expertise and teaching in a way that makes the material relatable for my students is what I enjoy the most at CVIF.

You are doing much more than teaching Earth Sciences at CVIF though!

Another advantage at CVIF is that it has research centers like the Research Center of Theoretical Physics, headed by Dr Bernido. And there’s the JACZ Marine Sciences Laboratory. When I arrived at CVIF, there was already an ongoing project at the lab but no one was working full time on it. Dr Chris Bernido and the late Dr. Maria Victoria Carpio-Bernido at CVIF had this proposal to study marine biodiversity at Jagna Bay, Bohol approved and funded by the DOST. What attracted me to the project was that it was a local study, but the vision was wide and far-reaching because it involved techniques like DNA barcoding. I really enjoy working with our curious and young team of researchers who are also teaching at CVIF High School.

We’re proud to have released a catalog of Marine Molluscs in Jagna Bay recently that details our findings from fieldwork sampling. The project is now in its second phase of implementation and we’re moving onto setting up a DNA extraction and amplification facility at Jagna to build a gene bank of molluscs from the Bohol Sea.

What’s next for you once this project concludes in 2023?

2023 will mark the 10th Anniversary of Typhoon Haiyan hitting the Philippines. I’d like to follow up work from my PhD and ask how long records of storm surges persist in the sediment, especially in tropical settings.

Let’s talk about your experience as a woman of color in STEM. Pursuing a career in academia comes with its unique set of challenges. Do you feel you have equal opportunities compared to your male counterparts? How has being a woman in science impacted your scientific career?

I don’t know if it’s just me but I didn’t feel much of a difference aside from that time when we were undergraduates and the mining industry and exploration industry catered towards men. I’ve never felt that as a woman in my generation I’ve had less opportunities than men in academia. In fact, geology departments in the Philippines tend to have a lot more women in teaching positions.

Is there anything you’d wish would change in your field to make it more inclusive for women of color?

I’m not sure if this applies to women in all cultures but in academia we’re so focussed on our careers that once you reach a certain age, you begin to worry about starting a family and this puts a lot of pressure on women. This issue of balancing our careers with our family life is very difficult to eliminate. I’m seeing more universities taking initiatives to help women to have successful careers while meeting the demands of their personal lives. In the Philippines, for instance, the maternity leave is now three months though it was much shorter, even five years ago. So things are changing and I’d like to see more efforts in this direction.

This brings me to my next question: academic careers can be very demanding. How do you take care of yourself on the daily?

I’ve slowly realized that I need to balance my time so that I can do more things outside of work. Walking outdoors, hiking, bird watching, gardening. I love cooking too. And watching sports. As I’ve gotten older I can no longer pull all nighters grading assignments. But I can totally watch the FIFA World Cup all night!

When you aren’t working, where can we find you?

At home. Either in the kitchen or more likely in bed. Watching K-dramas. Or browsing through memes on the internet.

Rapid Fire Round

What’s the first thing that comes to your mind when I say ‘earthquake’?

The first things I thought of were ‘fault line’, ‘shaking’ and ‘rupture’

If you were a tree/plant or an animal what would you be and why?

That’s easy- I would be a cat. So I can sleep longer, which is what I envy most about them

What two non-essential items would you want if you were shipwrecked on a deserted island?

A notebook and a pen because I’d be doing the geologic mapping of that island.

Photos courtesy of Janneli Lea Soria

Leave a Reply