Faye Romero

Faye Romero is a Filipino-American evolutionary biologist. She grew up in Sugar Land, Texas and earned her bachelor’s degree in molecular biology at UC Berkeley, where she used museum specimens to determine how hummingbirds have responded to human-induced environmental change. Currently, she’s pursuing a PhD in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Rochester, New York in Dr. Nancy Chen’s lab, where she is using genetics and computational biology to better understand the decline of endangered species, like the Florida Scrub-Jay. She plans to use her role as a scientist and communicator to increase the representation of Filipinos, Filipino-Americans, and other historically marginalized groups in evolutionary biology.

Let’s start by talking a bit about your childhood and where you grew up.

Guess I’ll start from the very beginning. My parents were born in the Philippines. They met at the University of the Philippines in Manila, got married and moved to the US in 1992 in search of better opportunities. They moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in Northern California, where my mom got an MBA. And my dad did his PhD in geoscience. They were both employed by the oil and gas industry, which is why we moved to Houston, Texas where I was born.

I’m the oldest of two siblings. My brother is four years younger than me and is at college in North Carolina right now, planning to study medicine. We grew up in Sugar Land, Texas, which sounds like a fake name, but it’s a small city outside of Houston. My parents, like many Filipinos, are Catholic. So while I went to a Catholic Middle School in America, Filipino culture was also a big part of my life. It’s a weird thing being Filipino American, because you have two different identities. And as a kid you’re always trying to figure out “Who am I?” My city and school specifically, was actually pretty diverse. We were lucky because we had a small community of other Filipinos in my city. So, like a lot of immigrant communities, it ended up becoming a large family of 40 odd people. We’d always do things together. Since the rest of the city wasn’t that diverse, this gave us a little haven and connected us to Filipino culture. When we were younger and travel was easier to coordinate, we would spend Christmas and New Year’s with extended family in the Philippines.

Tell us about your time as a student. Were there any subjects you particularly loved or hated?

When I was about 13, my parents got a job in Perth, Australia. We ended up moving to Australia for three years for their work and I went to an international school there. While leaving friends and community behind was hard and the culture was so different, it was a really cool experience. The focus on academics in Australia wasn’t as rigorous and competitive. It allowed both me and my parents to step back, relax a bit and connect with nature. This was also around the time that I started becoming more interested in studying biology after high school. I did my first two years of high school in Australia. And my last two in Texas. It was a bit of a shock to suddenly jump back into really intense academics.

Is there a person who you feel has been influential in you choosing your career path?

Growing up my dad was always really into science. When I was a kid, our bedtime stories were from encyclopedias and we’d learn all about the natural world from rocks to human anatomy to outer space. So I’d always liked the idea of biology and science but I’d never really linked it to a career path until I started applying to college.

I was a huge reader as a kid and did theater in high school. I thought then that I was meant for a career in literature or law. My parents, on the other hand, were very keen for me to pursue science or engineering in college. I think this situation is pretty typical for children of immigrant parents. Having worked very hard to create a life for themselves in a new country, the parents are keen that their kids follow stable career paths. Engineering and mathematics never came naturally to me. So we arrived at a middle ground with environmental sciences. I learned about grad school and academic research only during my undergrad. So I’d say my dad was very influential in my decision to pick science in college.

I ended up going to the College of Natural Resources at UC Berkeley for my degree. I’d never even thought about evolutionary biology until I took an evolution class. One of the teaching assistants for my class, Nicholas Alexander, noticed my interest and enthusiasm for the subject. He pulled me aside and asked if I’d be interested in helping out with a research project. He really inspired me because that’s when I realized that you can do science for a living.

I have seen how important it is to be a young mentor to young people. To have someone who is almost the same age as you believe in you and think that you’re capable of doing research and excelling in this field. I didn’t see many people who looked like me in evolutionary biology. I’ve met very few Filipinos in evolutionary biology over the last five or six years. So it felt good to be seen and encouraged in this way. I’m in the same career stage now that Nicholas was in when he helped me. I hope that as a graduate student, I can be a mentor to other undergraduates in the same way.

Let’s talk about your undergrad research project and how it motivated you to do a PhD.

I joined an evolution lab as an undergrad and I ended up absolutely loving it. I started working at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology on campus. It’s a closed research museum, only open to the public a couple times a year for educational purposes. The museum houses a vast collection dating back to the 1850s. There are a lot of specimens from California and the west coast of America. I remember seeing shelves over shelves of collections. For the project I studied Anna’s hummingbirds* and how they’ve changed in morphology over the last 150-200 years. I recall opening the shelf and pulling out 300 iridescent hummingbird specimens. And I just stood there thinking “Oh, my gosh! I get to handle these. I can’t believe I get to do this.”

I spent a lot of time- probably more than I needed to- going through the collections. I’d use the online database and ask “What’s the weirdest thing I can find?” I’d look up extinct species and I go find them in the collection. Or a sword-billed hummingbird and other really unique looking birds. It was so incredible to make all these discoveries on my own. When the project came to an end, I realized I wanted to keep doing this and that’s how I decided to apply to grad school.

*Anna’s hummingbirds are medium sized birds of the family Trochilidae that primarily feed on nectar from flowers using a long extendable tongue. The species is named after Anna Masséna, Duchess of Rivoli.

Did you have a project or study organism in mind when you began applying to PhD programs?

After my undergrad project on hummingbirds I thought about how cool it is to be able to look into the past, and see how evolution has progressed in such a short timespan (a few hundred years) and use that information to predict how populations will change over time. I love birds and bird watching so I’m definitely a bird person but I didn’t want to limit myself to birds while exploring labs for my PhD. I wanted to use genetics to study evolutionary change, something I never got to do as an undergrad. I wanted to focus on rapid change or anthropogenic change and connect that to broader aspects like ecosystems and conservation.

The research in Dr Nancy Chen’s lab is a great intersection of all those things that I had become interested in and I also got to continue working with birds!

Could you tell us more about your doctoral work and what you’re up to at the moment?

I’ve just started my second year at the University of Rochester, New York. PhDs in the United States are five to six years long on average so I have a long way to go!

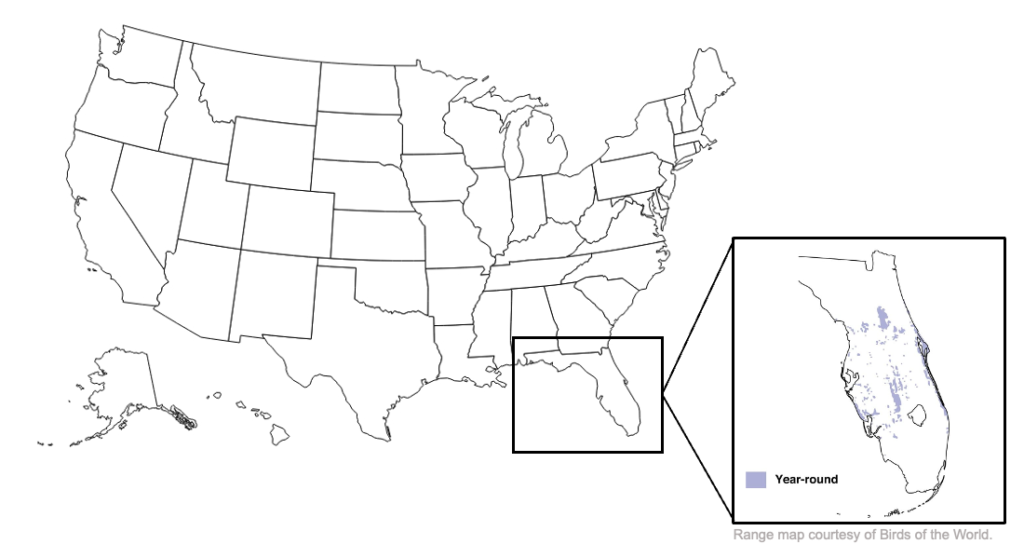

The primary study system in Dr Chen’s lab is the Florida Scrub-Jay. This bird is endemic* to the state of Florida in the United States. It’s found in a xeric** habitat that’s specific to Central Florida. In the past, there was a large contiguous patch of this habitat that all the birds could live in. With anthropogenic change and development, this habitat slowly became fragmented as people began getting rid of all the scrubs. Now this specific habitat only exists in very isolated patches across Florida, causing the Florida Scrub-Jay to become a Federally Threatened species. There are only about 10,000 of them left.

*A species is considered endemic if it is restricted to a single well-defined geographic area and not found anywhere else

**Xeric habitats refer to dry environments with limited water availability

How exactly do you study these birds?

There is a long term biological research station in the state set up in the 1960s specifically for monitoring small populations over time. The cool thing is that because it’s such a small population we can band individuals so every individual has been tracked and tagged. We have been gathering life history data at the individual and population level for many decades now.

Florida Scrub-Jays are corvids- they’re in the same family as ravens and crows. These birds are really intelligent and extremely social. So, unlike other birds, you can’t really capture them using nets. So we use peanuts to attract them and trap them temporarily into little cages. After tagging, the birds are released to go about living their normal lives. All birds are handled safely by trained individuals with the proper permits. I’m very lucky, because many people have already gathered a lot of data on every individual in the population. My own supervisor, Dr. Chen has been working on this system since her PhD. We have DNA samples of every individual within this population since 1989 and we’re currently sequencing all of this genetic data.

Will you then be using this data for your research?

What I hope to study is the genetic architecture of the small population decline. This population of Florida Scrub-Jays is relatively small, which can lead to a lot of inbreeding*. What we’re interested in is, how can we see this genetically, or using population genetics? How does inbreeding manifest in the genome and what specific regions are associated with inbreeding? An ultimate aim is to use this information to inform conservation practices. For example, there is some interest in potentially translocating individuals that are genetically dissimilar to combat inbreeding; this is a conservation practice that’s being heavily discussed and debated right now. We can try to answer questions like “How is genetic variation introduced and maintained in wild populations?” by identifying regions in the genome that are linked to inbreeding depression and reduction in fitness over time. This is what I and other lab members are working on.

*Inbreeding is the mating of closely related individuals in a population, while outbreeding is the mating of unrelated individuals.

Are you also teaching and mentoring students in your Department?

As a second year grad student, I’ve mostly been doing my coursework and working as a teaching assistant. I’ll be taking my qualifying exams* next year, in May or June. Running up to that, I’ll be developing my dissertation and my research questions. This information is ultimately sent to all the professors and other students in the Department for evaluation. Which is scary but also pretty exciting because once my exams are done, I’ll finally be able to focus on my own research and have more time to mentor undergraduates.

I’m a part of the Graduate Student Recruitment committee so I’m helping with the interview and recruitment process for incoming PhD students at my Department. I’m excited about this because I love interacting with young students interested in academic careers.

*Since this interview, Faye has sailed through her qualifying exams and is now a PhD candidate at Dr Chen’s lab!

Have you thought about what you’d like to do after your PhD?

I’m really open to different possibilities right now but I’d love to work at the intersection of academic research, education and science communication. I love museums- I started my career there- so my ideal position would be some sort of research affiliation at a museum. I can see myself continuing to teach and focus on communicating my science to a broad audience. I believe that it’s one thing to do good science but a whole other skillset is needed to communicate science well. I want to put my love of reading and writing to good use!

Let’s talk about your experience as a woman of color in STEM. Pursuing a career in academia comes with its unique set of challenges. Do you feel you have equal opportunities compared to your male counterparts? How has being a woman in science impacted your scientific career?

I’m very privileged to be in a lab where my PI (Principal Investigator) is an Asian American woman at a top tier research institution and I definitely see her as a role model. When I was applying to grad schools, I went out of my way to search for institutions and labs that had a mission of increasing the representation of women in STEM. Being a woman in a male dominated field, you’re constantly looking for a safe space. So even when I was looking for labs, I thought about where I felt the most comfortable. I’m very lucky because my Department has a lot of supportive women, which is not the case for many other institutions.

Being a woman in STEM is a topic that we aren’t afraid of talking about. My PI and I have talked about how easy it is for your idea to get lost in a conversation. I can say from personal experience, that if someone talks over me, I have to really fight my default mode of sitting back in silence. I’m actively trying to be better about voicing my ideas. Having other women in STEM around me, who have had similar experiences, as my support system has been very comforting.

Is there anything that you wish that you could change in your field to make it more inclusive for women of color?

I’m so grateful to have had parents who could provide well for our family and who encouraged me to pursue a career in STEM. I sought out a young female PI of color as my graduate supervisor because I felt like that would be a safe and comfortable environment for me. Seeing even a handful of women of color be so successful in my field has been very inspiring for me. Hopefully, this will move down the chain over the years and we’ll see greater change in the demographics. I think we need to talk more about diversity and representation at the administrative level. A lot of conversations around this topic are happening among graduate students and faculty. We are constantly working towards making topics of diversity, both in race and gender, less taboo. Taking these up to the administrative and departmental levels is the only way to see institutional change.

Academic careers can be very demanding. How do you take care of yourself on the daily?

I’m very much still working on this. There is definitely a culture in academia of overworking. The prevalent thought is “the more you work and the more you sacrifice from your personal life, the better of a scientist you are”. If you’ve spent all weekend in the lab, then you must be really dedicated. I still operate under this notion where if I’ve worked late into the night for the entire week, that must mean I’m doing well. Which is not necessarily the case.

This semester has been the busiest time in the last four or five years in my life so I’m trying to find ways to balance my work and personal life. As a computational biologist, because you always have your laptop with you, you always have your work with you. I’m now trying to establish a distinction between my home and work time. I live with my partner who has been a great support system in pointing out when I have been working a lot, when it’s time to take a break and also take pride in what I’ve achieved.

Dedicating time to hobbies has also helped me: I’ve taken up crocheting recently. I love to dance. I do social dancing, which is something that allows me to step away from work and interact with people.

When you’re not working, where can we find you?

I really like spending time outdoors when I can, although it’s pretty cold here right now and I’m bad at being outside when it’s cold! When it’s warmer, I love to birdwatch and go on hikes. I also love watching movies. I’m big on science fiction and fantasy. I’m catching up on all the Star Wars shows right now.

So movies, being outdoors, crocheting and dancing. That’s me summed up 🙂

Rapid Fire Round

What’s the first thing that comes to your mind when I say ‘birdsong’?

I thought of White-crowned sparrows* that are these really interesting birds that have different dialects across the US.

*Here’s a sound bite from the media organization BirdNote about these dialects.

If you were a plant or an animal what would you be and why?

I’d love to be a whale because I want to see what’s deep in the ocean.

What two non-essential items would you want with you if you were shipwrecked on a deserted island?

I’ll take my current crochet project because that’ll fill my time if I’m bored. I’m making a really long mustard yellow scarf right now! And then maybe some music on an old school Walkman or a small iPod that I can dance to.

Photos courtesy of Faye Romero (unless specified otherwise). All birds handled with the proper permits.

Leave a Reply