Ariane Peralta

Ariane Peralta is an Associate Professor of Biology at East Carolina University located in eastern North Carolina, USA. Ariane attended the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign to earn a BS degree in Biology and Chemistry and MS and PhD degrees in Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology. Ariane’s dissertation examined how hydrologic changes during wetland restoration efforts affected microbial community structure and nitrogen cycling functions related to enhancing water quality. Then, Ariane moved on to a postdoc at the Kellogg Biological Station at Michigan State University and the Department of Biology at Indiana University. During this time, Ariane was awarded a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture to study the consequence of long-term cropping diversity on soil microbial community structure and disease suppressive function in soils.Since 2013, the Peralta Lab at East Carolina University has been examining how climate and human-induced environmental changes modify nutrient and water cycles to influence environmental microbiomes. The research team uses laboratory- and field-based approaches to study how climate and land use changes influence microbial community structure and functions associated with regulating air quality, water quality, and human, animal, and plant health. The Peralta Lab also conducts interdisciplinary microbiome research and collaborates with economists, engineers, geologists, and anthropologists to understand how ecological systems interact with human systems to better predict how microbial communities will respond to environmental changes.

Let’s go back to the beginning, could you paint a picture of your childhood for us? Did you have any siblings? What was a typical day like for you when you were growing up?

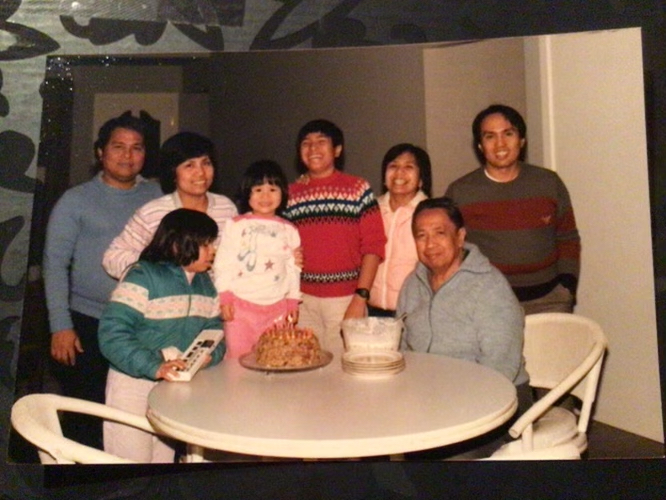

I was born in the Philippines in Manila, and we emigrated to the US after I turned one-year old. My family ended up relocating to Northwest Indiana, outside of Chicago. We went from a very tropical, warm place to a bitterly cold place. Some of my early pictures are of me in a snow suit. I went with my mom, her siblings, and my grandfather first and my dad and cousins came over a few years later. We’ve been in Northwest Indiana since and that’s where my family still resides today. I grew up in a multigenerational household with my grandfather, aunts, uncles, and cousins. It wasn’t until I was in elementary school that my parents and I moved into a different house just one block away. We were able to recreate some of that family connection that we had in the Philippines, which was magnified by many households, within our little family in the US. So, when I think of immediate family, I don’t think of just my dad and me. I think of all my cousins, aunts, and uncles, and family friends.

On a typical day, I remember a lot of time around the kitchen, and food, because that’s essentially what brings all of us together. I grew up in a really loud household, with laughter and a lot of kidding around. Maybe some might call it too much teasing but that gave all of us a very strong exterior. I’m an only child, but I grew up with my older cousins. They were five and seven years older, and so they wouldn’t pick on me. In fact, I looked up to them, but I remember them fighting a lot because they were closer in age.

Did you wind up going to school in the neighborhood?

Yes. We were in a primarily white town in Northwest Indiana. The few Filipino families we knew sent their kids to Catholic schools or private schools. But me and my cousins went to public school. We had a good public school system. So, I grew up going to a school that was one to two miles away from where we lived.

While you were growing up, were there any subjects that you loved or hated in school? And did you gravitate towards the sciences early on?

I did gravitate toward the sciences early on. I would say classically, math and science. I also really loved music. I was in music classes and took a liking to a lot of different instruments. I was always trying to balance music and STEM. Both those identities have followed me throughout my career.

Was there one person, or a group of people, who influenced your choice of this career path?

I would say I didn’t really know about being a research scientist back in the day. I think I was drawn to elements of it. My mother, Iris Legaspi Peralta, who passed away before I got into high school, was a family doctor. She had me during her residency and essentially raised me while she was still in training. She went into an area of medicine that was about the people. She took care of the entire family. And I just remember times where I would be in her office, and it’d be after hours. And this was a time in which you still had small family practice offices. Families would come in and they would bring in food or cake or whatever. Even if someone couldn’t pay she wouldn’t turn them away. During this time, family doctors were also delivering babies. I remember going with her to the store to get a gift for the patient that she was going to go see who was having a baby. Those are the things that I remember. I forget a lot of things growing up. But some of those first instances seeing her as a professional definitely made their way into how I approach my career. I saw that and grew up with that service forward idea of being able to use your science brain to help people.

I was always interested in medicine, I would say mostly because of what was around me. It was more of the science of what was happening within medicine that I was actually interested in and that I didn’t know about until I got to college. I just remember early on doing projects focusing on disease and outbreaks and my mom helping me do research. I really geeked out on it. My recollection was that she always supported me. Education was very important- and an expectation- in my family – we were often reminded that my maternal great grandmother was a teacher and grandmother was a pharmacist. So, I already saw that glass ceiling broken. And because of the folks that went before me, I knew that I could pursue a career in STEM too.

Was there any particular moment in your life when you felt a pull towards being a scientist in your field of specialization?

I came into college thinking that I was on the path to do an MD/PhD, so more of a scientist position. I don’t know why I knew that that existed. I chose the University I went to because of opportunities to do research as an undergraduate and also because they had a really well-known history of a lively independent (‘indie’) rock music scene. I knew I was going to be able to do both if I wanted to. I came in as a bioengineering major, mostly because my dad studied engineering and my mom was pre-med, but I found my way to a major that was research focused. It was in biology, but it was very much grounded in strong quantitative and research-based opportunities and classroom activities. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign was really big. So, to be in a major with 30 people throughout your time was something that I was very excited to learn more about.

This idea of a hidden curriculum, this hidden knowledge of what you’re supposed to know, before you get to university is something that I noticed right away. Even though my cousins went to university in the US before me, I would say that they chose a more obvious and established career path in healthcare. So when I learned that there was a research-based major that I didn’t have to apply to before getting into college, but that you applied to get into the major after your freshman year, I was so excited to apply. I would say finding that major and co-curricular activities that help you hone your interests is critical.

As far as my interest in ecology and environmental studies goes, I didn’t know much about this area of STEM until I took organismal biology. We had a guest lecturer in our biology class who studied climate change research and forests. They were sharing their work on experimenting and manipulating concentrations of carbon dioxide on whole forests! This was the time when free air carbon enrichment studies, also known as FACE studies, were getting established across the US and also globally to understand whole ecosystem responses to climate change. When this profession shared the fact that you can manipulate whole ecosystems and increase carbon dioxide to understand what is going to happen decades from now, I was totally engrossed. I did not know any of that was happening and how important it was. I reached out afterwards and asked if they had any research opportunities.

During this time, I was working in a neuroscience lab, and I maintained that connection throughout my undergrad for three and a half years. But during summers, I worked in environmental sciences and ecology. Since the professor who studied plants and climate change did not have any space in their lab, I was encouraged to contact one of the collaborators who studied soil science. I would have never found my way to that lab, studying soil science, soil ecology, and sustainable agriculture, unless I had sat through that class, and then reached out and asked about opportunities. I ended up working in Dr. Michelle Wander’s lab during undergrad, and I ended up doing my Masters in the lab too. It was definitely a critical time for me to think of myself more as an ecologist.

For any young students who are thinking of a career in microbial ecology, what kind of courses did you study at university as an undergrad?

I did a lot of intensive lab-based courses that were open-ended which were so much fun. We studied ecology in the third biology class of the honors biology series. And I loved it. The stream lab, outside in waders in the winter, was so memorable. But I didn’t see myself as an ecologist or a microbiologist at that time. My first (and only) undergraduate microbiology class was bacterial pathogenesis which didn’t expose me to the microbial diversity we study from an ecological and evolutionary perspective. I think that a master’s degree was really critical for me to not only read more about the field but to learn more about what microbial ecology is, and soil ecology was the gateway to that, because the processes we were studying were microbially mediated or driven by microbes. And during that time, the technology to study microbes outside of the petri dish was increasing.

What I learned is that I needed to be open minded and willing to take courses or to read content that were completely different from each other. If I wanted to understand how to analyze data, I needed to do a lot of statistics and experimental design. If I needed to understand how different climate change variables affected the biology, I had to know how to evaluate that. I think that experimental design and statistics were topics that I loved right out of the gate during undergrad. We had to take an advanced statistics course during undergrad. I think that helped me get a foothold as well, because that really sparked my interest.

In terms of what courses to take, I’d say ecology and evolution. No matter what you’re going to go into in STEM, you can’t study and understand biology out of context. Even in medicine, understanding how humans interact with the environment is essential. How organisms change over time such as microorganisms becoming antibiotic resistance- that’s evolution. So, when I teach a microbiology class of mainly students interested in health care professions, they’re still surprised, but I definitely take an ecology and evolutionary biology approach to microbiology, because it’s so essential for us to meaningfully understand the system.

Which field did you go into for your masters?

Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. I stayed in the same institution for all my degrees, but I changed research areas. And I took time off in between my masters and my PhD as well. My master’s degree is in biology, but with a concentration in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

What was it like to stay in the same university? Did that give you some sort of continuity in what you were doing, or provide you a comfortable environment to really flourish?

I would say both. At the time, and even now, there is stigma associated with staying in the same institution and I understand why that exists. However, if you demonstrate that you’ve learned different skills and in different topic areas, I don’t think that should dissuade somebody or should put a stamp on you that says you’re closed minded, because people have many different reasons for staying and choosing a particular academic institution. After I got a review back from a graduate fellowship, it was clear that the reviewer did not read my application but only noticed that I went to school in the same place. The reviewer emphasized how I stayed at the same institution for my training and that I probably don’t have the breadth of training and experiences required to be successful.

One of my decisions to stay was because I was in this rock and roll band, and we were touring in the UK and playing gigs in the Midwest during my undergraduate and MS degrees. I didn’t want to stop school, and I didn’t want to quit the band. So, I stayed at the same University. I wasn’t trading off with being able to do cutting edge science. I was still able to do that. I just didn’t go for research experiences to Alaska or other off site places in the summertime, for instance. I still did research, but it was locally. I made some intentional decisions that helped me continue on my STEM path but also allowed me to keep being a musician at the same time.

Wow, that’s fantastic! Do you want to talk a little bit about your band?

The band that was called The Beauty Shop. We were a three-piece band. It was a cross between country and rock, more specifically in the ‘alt rock’ or ‘Americana’ genre. I played the electric bass. The band was led by singer-songwriter John Hoeffleur who played the acoustic guitar and different members who played the drums. We were pretty stripped back. I remember answering the ad that they were looking for a bass player, it was a handwritten flyer advertised outside one of the science building. I didn’t know half the bands they listed as inspirations, and I shyly called home and asked my old bandmates if I should try out. I had been playing covers of other people’s music during high school, and we played a lot of parties. In college, I didn’t think that it was going to go anywhere past playing at the coffee shop or clubs, but it did. We recorded albums and played at different venues. It was interesting to balance that life, being serious about practicing and playing gigs, playing at 1 am and then going to class the next day. I was an out of state student and there was no way I was going to skip class – I was getting full value out of my education. I might have been sleeping a bit during some classes, but I was definitely there. I think it helped me balance different obligations that were really important to me.

There were a lot of parallels to being a touring musician and being a scientist. A lot of the do-it-yourself mentality carries over; nobody’s going to advocate for you but you. We had to create our brand, we had to make sure that we were prepared to play the best show that we could every time, because you don’t know who’s going to be in the audience. We were creating music and making CDs and sending them to places that might be interested in distributing them. So, a lot of what I didn’t think were experiences that have anything to do with a STEM career later, totally give me an edge now.

Being open to any kind of audience is also such an important skill.

Yeah, I talked to a lot of different people. We sold t-shirts and CDs. I think it also helped me be less shy. It made me stronger. Maybe I was shielded a little bit from the challenges women in science face because of music but also because of my family experiences.

Coming back to science: the work that you did in the summer during your undergrad, did that carry over to your masters in ecology and evolution?

When I was an undergrad, I was helping graduate students with their thesis and dissertation topics. We all used similar approaches to understand how different land use changes to the soil environment influenced the type and amount of carbon getting stored in the soil. I did not know all the intricacies of how important soil carbon was and how difficult it was to study at the time. How critically important it is to promote soil carbon storage, while also being able to grow food. Being a part of that lab, and mentored by Dr. Michelle Wander at the University of Illinois. I also had the privilege of working with Michelle’s husband Jon Cherniss, successful organic farmer and owner of Blue Moon Farm in Urbana, Illinois. These research and on-farm experiences were really critical for me to wrap my head around why soil organic matter is important in context of food, climate, and policy. I remember being in a room with graduate students who were so passionate about sustainable agricultural management. It was just a great experience. We were mostly all women in the lab at the time and our advisor was the first woman to be hired in the soil science department.

I remember how welcoming and kind everybody was. Even though you think you don’t belong, being in a welcoming environment helped me overcome those impostor feelings. Those are all positive experiences that helped me continue onto graduate studies. I moved to examining the interactions that plants have with soils and microbes. You have to know about chemistry, physics and biology. It was this integration of all the foundational courses that I did in undergrad that was really exciting.

You mentioned these FACE experiments.

Yes, free air carbon enrichment (FACE). I had the opportunity to conduct research in a newly established FACE site that focused on the corn/soybean rotation for my masters. The question had to do with how elevated carbon dioxide and ozone concentrations treatments influence soil organic matter (as a consequence of changes to plant physiology and productivity).

How do you do an experiment like that? Is it in a greenhouse?

No, it’s out in the field. There was PVC piping that had holes in it, and carbon dioxide (and later ozone) was pumped into the specific area that we were studying. There were sensors to know where the wind was blowing, so the gas enrichment would ‘wash’ over the study area. Technology made it possible to move from greenhouse closed chamber experiments out to the field. My Masters focused on understanding changes in those early time points. At the very beginning before the experiment started, and three years later.

So, you participated in this cool FACE experiment during your masters. And then you decide to take some time off before you start your PhD. Did you work at the organic farm during that time?

I worked at the farmers market a little bit, selling vegetables. But I went on tour with the band. I was working as a lab technician, which kept my hours flexible. I pivoted to prioritizing a little bit of time away for my music, if we needed it. That time confirmed that I should go back and be a scientist. I would read journal articles at the bar while on tour. I knew that I wasn’t going to be playing music long-term. We did a reunion show in 2016 when I was already a professor here at East Carolina University (ECU). So, 10 years after I stepped away from the band and started grad school. We did one reunion show. I flew out to Champaign-Urbana. We practiced once and then we played, and it was really fun!

How long was the break? Was that a few years or a few months?

It was about a year between finishing up my MS degree and starting the PhD program. During this time, I was a technician in a new microbial ecology lab and ended up staying in that lab for my PhD. I brought my soil ecology experiences into a lab. I think that was helpful for me to experience what it would be like to be the technician, in contrast to being in a leadership role. My affinity towards leading projects helped me make the decision to go back and get my PhD, because I wanted to be in charge of my research agenda.

And what was your PhD on?

I focused on the microbial ecology of wetlands restoration. A lot of wetlands in the Midwest have been converted to agriculture. Some lands were then taken out of agriculture and entered into conservation reserve programs. This was because of a mandate that if you were going to destroy a wetland for development, for example, if you’re going to build a road through some wetland, then you have to restore a wetland of equal size somewhere else. This policy of no net loss is mandated because of the Clean Water Act in the US. Researching wetlands was ecologically important but also a policy relevant type of ecosystem to study.

My dissertation was on trying to understand how previous management of the land, while it was in agriculture, influenced the microbial ecology of the restored wetland soils. The surrounding water cycle and nutrient cycles had completely changed because of human influence. Microbes are critical at converting nitrate to di-nitrogen gas through the process of denitrification. Wetlands are really good at providing habitat for microbes to carry out denitrification. The idea of ecosystem services and ecosystem benefits is something that was really interesting to me. I wanted to mesh ecological questions with applied restoration and policy relevant questions. There were a lot of assumptions that were being made about how wetlands were functioning but little was known about the microbial majority that lived in the soil.

Wetlands are defined in different ways but essentially, they’re the areas between the land and the water. The classification is based on whether water-loving plants are there, whether soils are saturated throughout the year, and how much water is present over a given amount of time. The identification of wetlands from a policy standpoint had nothing to do with microbes. The assumption is that if you flood a system, you’ll get the microbes that are doing this job of promoting increased water quality. Essentially, taking that nitrate out of the water and soil and then converting it to an inert gas is the ecosystem benefit that is assumed to be provided by wetlands. But wetlands could also be producing greenhouse gases. There are potential tradeoffs that we’re not measuring. I wanted to understand what the microbes are actually doing in these restored versus natural wetland ecosystems. And are we restoring microbial communities in a way where they’re functioning to their pre-disturbance levels? And the answer is no, but they’re still there. They’re carrying out these water quality functions, but it’s a different community of microbes. And they’re functioning at rates that are not at levels that were measured in natural wetlands.

When did you finish your PhD? Did you go straight into a postdoc after that?

I finished my PhD in 2011. I worked on the organic farm and a wine shop in between the time of defending my dissertation and starting the postdoc. I was essentially trying to figure out the funding for my postdoc. I knew where I wanted to go and had already started writing grants with my future advisor. It was just a matter of time that I would have to wait. I wasn’t willing to take up a postdoc in an area I wasn’t interested in.

It’s risky to not always be in a STEM position. I was at a critical point where I could have easily left STEM if I wasn’t careful about what my next move was going to be. I give kudos to my postdoc advisor Dr. Jay Lennon. We’re still collaborators and friends to this day. Jay demystified the prospect of being an academic researcher. I didn’t start my PhD to stay in academia. On the first day of my postdoc, Jay asked me what my favorite parts about being a scientist were. I really liked designing experiments, working in the field, working with students, writing grants and papers. I like data analysis too. And he went “That’s a professor’.” He essentially helped me see what I wasn’t seeing. I knew that I needed to improve my proposal writing and my postdoc advisor was just excellent at those things. It was an enriching and encouraging space to continue my science journey.

Just out of curiosity, how long did you take off?

I defended my PhD in May 2011, but I turned in my dissertation in November and then started my postdoc at Kellogg Biological State, Michigan State University in December. So I took about six months off.

What was your postdoc on?

Initially, it was on how different organic, sustainable agricultural nutrient management influenced soil food web structure and soil organic matter concentrations and storage in perennial wheat systems. It was the project that first brought me to the biological station at Michigan State. Then I wrote my own grant submitted to the US Department of Agriculture as a postdoc fellow. I was at a biological station that maintained many different long-term ecological research experiments for over 25 years, trying to understand the role that both climate and also human management played on agricultural ecosystems. I really geeked out on one of their experiments that had to do with cropping diversity, trying to understand how increasing crop diversity over time (also known as crop rotations) influences soil microbial communities in ways that contribute to plant health. I was focused on how soil microbial diversity responds to cropping diversity, with specific emphasis on disease suppressive functions such as antimicrobial activity.

Did you move close by for your postdoc? Or was this far away from where you did your PhD?

I did my PhD in Illinois, two hours south of Chicago. And then I moved to Michigan for my postdoc, only a couple hours in a different direction from where I grew up. When I was in that lab for a year, the lab moved to Indiana. I was doing experiments both in Michigan and Indiana, but I got my job here at ECU pretty quickly.

And how long was your postdoc?

Two years. I started at ECU in 2014. I began applying to jobs within the first year of my postdoc.

Was it very different moving institutions, from after your PhD into your postdoc? And then once you started as an Assistant Professor?

It wasn’t so different, moving from PhD to postdoc in terms of the kind of research or the kind of institution. But when it comes to the institution I’m at now, it is a little bit different.

The other schools I grew up in scientifically were all agriculture-based schools. Their mission had to do with sustaining agriculture for that state and were very research intensive. ECU is still research intensive but a lot of value and emphasis is placed on teaching. The integration of both teaching and research is a really good fit for me.

Trading off with providing research opportunities for a range of different students is something I don’t want to give up. I like to think that teaching and research can go hand in hand. I really like being in a place where spending time on making sure teaching and mentoring is valued and appreciated without it feeling like a tradeoff. We have a really special community of scientists here that are truly interdisciplinary, working on both ecological and also the human dimensions of the system.

It doesn’t have to be basic versus applied sciences either. The fact is that you can do both if you want to or be in the middle. Being at that interface helped me see the type of research program I wanted to maintain in a creative way.

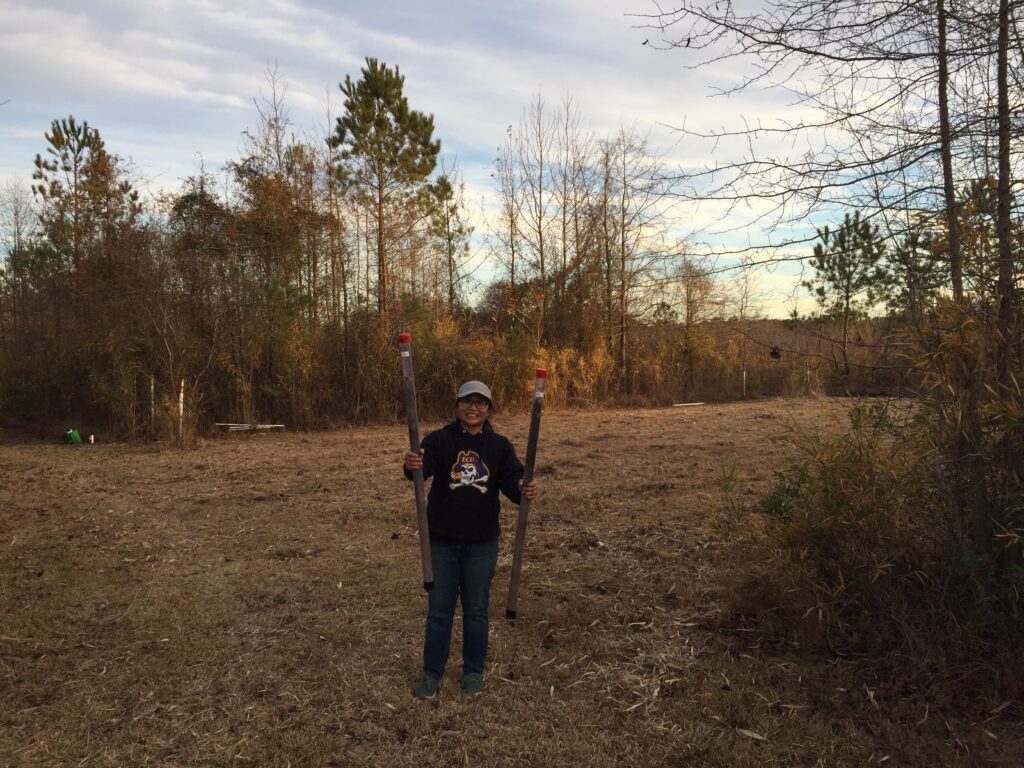

On that note, could you give us a summary of your work in microbial ecology at your current institution?

Our region experiences a lot of storm surges, sea level rise and atmospheric deposition of nutrients. We are in a hurricane and tropical storm prone area. Because of industrial agriculture and other industries, this area becomes a hotspot of nitrogen deposition. Many ecosystems across the US and the world are experiencing something similar. Ecosystems that were nutrient starved, historically, are now being fertilized. The question that I wanted to ask was how this increased fertilization of wetlands due to different climate change and land use change drivers affect the ability of wetlands to store lots of carbon. When you add fertilizer to anything, it makes things grow and forces a lot of microbes to increase their rate of metabolism resulting in carbon losses as carbon dioxide.

When I interviewed here at ECU, I learned about a long-term experiment that had been started 10 years prior and had to do with the fertilization of wetland ecosystems. This experiment was started by Dr. Carol Goodwillie at ECU. It provided this great infrastructure and opportunity to study what was happening between the plants that have already been surveyed every year by students, and the consequences of that on both the soil microbes, plant-microbe interactions and the soil’s physical and chemical properties.

This ecosystem is critically important for climate change mitigation and habitat for biodiversity. Are we overestimating the amount of carbon that we’re storing, because we might be increasing the activity of soil microbes and potentially disrupting this cooperative relationship between plants and their microbial partners by adding nutrients to the system? We’re exploring this question using multiple approaches. Some of the work is culture-based, where we grow soil bacteria in the lab. We’re adding different simplified bacterial consortia to wetland plants along a fertilization gradient to understand if we can demonstrate positive to commensal, to negative responses of plant growth. We’re doing simplified experiments in the lab. We’re also doing environmental DNA characterization to understand what has been happening over time to the relationship between the microbial below ground with the plant community above ground.

There are other parts of our research program where we collaborate and the leads are economists and engineers. In the US, if you are in a rural area, there might not be infrastructure available for municipal water. Typically, households have their own private wells. But there is no federal policy on protecting the water quality of these wells. After you drill, you have to test your water, and it has to pass certain regulations by an Environmental Protection Agency but there’s just no funding for, or emphasis on, retesting. Our team is trying to understand the patterns of water quality in this landscape. The idea is to use different modeling approaches to understand how water flows through the landscape and how land uses change through the landscape and how these features relate to the health statistics and other demographic information of an area. We’re using these updated models to predict hotspots of potential contamination based on coliform bacteria or nitrate concentrations in drinking water. We plan to communicate the level of risk to particular communities and potentially inform future policy on groundwater drinking wells.

There are so many different aspects of microbial ecology that your group is involved in exploring! What role do you play in this water quality project?

I’m the biologist on the team. I also understand soils and how water moves through soils. At the end of the day, I try to keep us in check. Not all microbes are pathogens. So, we need to think carefully about what these data actually mean.

I also am involved with some marsh restoration work and understanding how we can promote plant microbe interactions to enhance the establishment of coastal marshes and their success after planting in pretty stressful environments. This is a newer area of research. One of the big reasons why I came to ECU and why I continue to stay is the opportunity to do interdisciplinary projects on a basic to applied science continuum.

What is it that you’re most excited about your current position at ECU?

I’m excited to continue working on climate change and microbial feedbacks, both in basic and applied microbial ecology. We’re at a location where there are multiple stressors: a lot more storms, increased salinity, extra nutrients. The relationship between people and land is important as well. So, this push and pull of natural resources as well as agriculture is happening in a small watershed (our backyard), which makes it more tractable.

Being at a place like ECU allows for this community engaged research component. Working with communities, learning about what communities want to know about their environment, and what their issues are with water quality, for example, provides that real-world context to some of the questions that we’re trying to address. It’s both an opportunity and a challenge to work in a space that involves humans. Working in an intentional manner that brings in trainees, students and other interested parties to the table has been really fun.

I get to work with a wide range of students. Nearly 50% of them are the first in their family to go to college. A lot of my colleagues are also the first in their family to go to college, and they’re now their professors. For me, seeing that play out is really special.

It sounds like such a wonderful place. What are your plans for the future?

In terms of the science, there are many different things happening. I’m even involved with hosts-associated microbiome work. We have a lot of organismal biologists in our department and the gut microbiome is something that people are really interested in. We use the same tools so enabling graduate students to get into that field has been a lot of fun as well and I’d like to continue on this path.

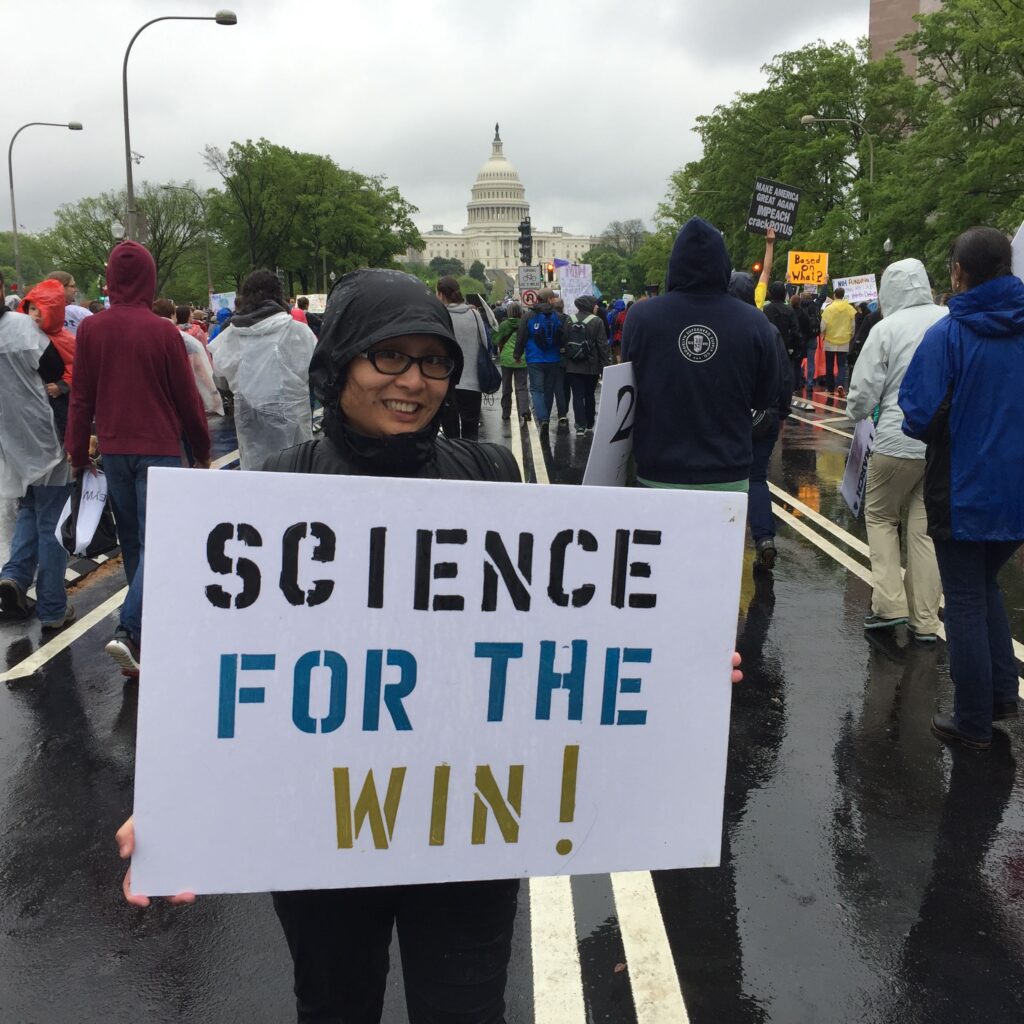

Do you feel, throughout your journey, that you have had equal opportunities compared to your male counterparts? How do you think being a woman has impacted your scientific career?

We know that there is a bias against women of color, particularly in STEM fields. Knowing that at the outset was useful, but it didn’t mean that I was offered a salary on par with my male counterparts at that time. But then you start making excuses. “Well, I was really new.” “I was only one year out of my postdoc. So maybe it was because of that.” or “Because I’m a biologist and not a biomedicine type or the kind of ecologist who does a lot more molecular sciences.” So, a lot of excuses for the fact that maybe it wasn’t equitable at that stage. But it just made me more persistent. I love writing grants. What my experience has taught me is that if your ideas are good, you believe in your team, and you’re excited about the work then just keep improving and re-submitting those grants, and eventually you’ll get funded to do the exciting work and support training of early career researchers.

Thinking of the glass as half-full helps me to continue to be really aggressive with getting funding, not in a way that squashes people, but in a way that I hope builds our programs. I want grants so that it funds the research in my lab but I also want grants to enable more students to be paid to do research during the academic year and in the summer. I try to recognize challenges we might have and then try to do something that I know is within my skill set to help move the needle forward a little bit. That’s something I’m not shy to do.

If I’m in a room with administrators, I’m going to say “It doesn’t matter if that’s the way it’s been done. It doesn’t mean it’s right.” Trying to balance calling people out and calling people in is something that I continue to practice. If I continue doing this work to help improve our programs to be more accessible and inclusive, for me, that’s worth the extra work.

As a professor, I am able to do the research I want to do, grow my program, and enhance our programs at the university as well. I also try to build my mentees to be thoughtful about both their place and finding their way through STEM, recognizing their privilege and power and using it in different ways.

What would you wish would change in your field to make it more inclusive for women of color?

I’d say work to retain more mentors of color. If you see the makeup of my lab, for example, it’s pretty clear that there’s something about my group – folks are getting recruited into and staying. For example, there are many women of color that have come through my lab. Maybe it’s helpful that I’m a person of color myself but I’m also very intentional about working with students and meeting them where they are.

It is difficult and challenging to work with folks that are from varying academic levels. Not everybody has to do an independent project, but everybody could learn from doing research. So, whatever that looks like, it’s going to be different for every student. I think being open minded about the role of both student researchers in a classroom and independent researchers working in your group, is something that I am hopeful will change over time.

There’s also a perception that if students don’t come from a certain academic background or experience level, they’re not going to be able to do certain kinds of science that we do, which I think is absolutely false. It just takes a different approach. This type of inclusive research and mentoring is something that I’m on the road to helping illuminate.

What advice do you have for women of color who are just starting out or thinking about careers in STEM?

Don’t be shy to advocate for yourself. Start building your network of both peers and potential mentors who are supportive. I think we’re much more connected now than we were even five years ago. I think these connections are all critical for helping sustain going into this work.

The majority of male counterparts have always had a network. That has definitely shifted power and prestige. Equally, we also have these networks that are strong and supportive. Pursuing those, sharing your experiences with others and being generous with time, with the exchanging of ideas, I think that’s really our superpower.

Rather than it being “There’s not enough room for folks.” I think there’s plenty of work to do. Building people up and helping them achieve what they want to achieve is essential. Acknowledgement that we all have impostor feelings that will just grow and will never really go away is really important to discuss. As women of color, we are more likely to have had experiences that help us be more resilient and persistent. These are important for overcoming challenges. Just changing your mindset can be really powerful.

We know that academic careers can be very demanding. How do you take care of yourself on the daily?

I really enjoy casual interaction with both colleagues and friends, whether at work or with folks that I’ve worked with in the past. I strive to stay connected with everyone. It’s hard to separate work and home because a lot of my good friends are collaborators. I love to make interactions happen around food and drink.

And I put together a lot of jigsaw puzzles. That is useful for winding down and making your mind work. I multitask, perhaps too much, so my focus on things could be improved. I think that doing a puzzle helps me focus. I really enjoy that even if I’m on vacation. When we’re all at the beach with friends and family, there’s always a puzzle going. I also like listening to books. A lot of audiobooks. Music is all around too. But with the pandemic, I don’t go see music as much as I did but that’s starting to change.

I exercise in the morning mostly. It’s good for your health, of course, but mostly because I enjoy eating so much. 🙂

When you’re not working, where can we find you?

At my house, probably hanging out with my dog or making puzzles and hanging out with friends.

Rapid Fire Round

What is the first thing that comes to your mind when I say ‘bugs’?

There are some microbiologists who refer to microbes as bugs, which I don’t like. As an ecologist and someone who has friends that study taxonomy, bugs are insects. So, for me, this word brings back how annoyed I feel when I hear the word bugs being used to describe microbes, which could be bacteria, archaea, microeukaryotes, viruses or fungi.

If you were a plant or an animal, what would you be? And why?

Honey badgers, because they never give up.

What are two non-essential items that you’d want with you if you were shipwrecked on a deserted island?

A musical instrument of some sort and a puzzle. Anything that would help you get food or water would be essential, so I’m not going to say cutlery or some kind of weapon or sunscreen. This is what happens when you ask a scientist!

Photos courtesy of Ariane Peralta

Leave a Reply